By Jim Gallagher

May 30, 2017

For the past few years, my far north paddling partner Brian Johnston and I have kept a rather fluid list of Arctic rivers and routes that we haven’t yet explored. Potential rivers get added or deleted depending on a loose set of criteria. We try not to overthink the process and let the best opportunity float to the surface. Any chance to paddle a tundra river is a good one.

Brian Johnston and Jim Gallagher on the hills overlooking Franklin Bay at the end of the Horton River.

The Horton was a river in the ‘old man’ category on that list – a relatively easy trip saved for a year when more demanding routes were beyond our desire for hardship. In 2016, an opportunity to share a Twin Otter charter flight with four Ontario-based paddlers helped to make our decision to paddle the Horton River.

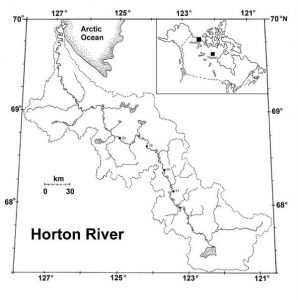

Located in the Northwest Territories of Canada, the Horton River flows for 375 river miles from Horton Lake to Franklin Bay on the Arctic Ocean. Horton Lake is not the source of the river, but it is the most common starting point for paddlers.

The Horton is not a technically demanding river to paddle. The only rapids along its length are within three canyons that lie about half way down the river. We scouted and ran rapids in the first and second canyons. In the third canyon, the combination of several rapids and a ledge demands either a portage or utilizing nearly a full set of moving water skills to negotiate. We ran rapids, lined others, lifted over a ledge, and executed an upstream ferry across a strong wave train in this canyon.

Much of the river flows through a landscape dominated by limestone rock. Cold water seeps and creeks flow from hillsides. Unique pillars, canyons, and other rock formations are common. The water remains clear and sweet to within 95 miles of the coast where it becomes cloudy and bad tasting – affected by the burned coal and mineral runoff from the Smoking Hills.

On the River in 2016

The northernmost reaches of the boreal spruce forest follows the Horton River valley north almost to the Arctic Coast. Beyond the valley, the barren lands begin. The wildlife following the forest blends with species at home on the tundra. Arctic terns shared the sky with the red-breasted American robin. Nearly every bluff wall and canyon had huge stick nests created by bald and golden eagles. Tiny woodland warblers familiar much further south called from thickets. Their songs seemed out of place at this latitude. We were north of the Arctic Circle and getting further north every day.

Jim holds an Arctic char caught in the cold water of the Horton River.

For the first two weeks it hardly felt like we were traveling on an Arctic river. Temperatures soared into the 80’s. We renewed our baptisms in the river with daily swims. In communion with the river, we ate char, lake trout, and grayling caught in the clear water. Others were caught and released. Their strong hearts beat against the hands that cradled them in the water, gently sliding them back into the current. Each fish flashed bright colors in life – subtle purples, pinks, and deep gold. Each was like a jeweled work of art – fat and writhing.

Where one cold creek entered the river, hundreds of grayling, char, and lake trout congregated in the transparent outflow. Swimming slowly in place, they pushed against the current seemingly relishing the frigid water.

A mother grizzly bear stands to get a better look at Brian and Jim passing by on the river.

At a bend in the river we came upon a mother grizzly bear with her two cubs. She stood up to her full height to assess the danger to her offspring. We floated past them in our canoe, separated by a hundred yards of river. A telephoto lens closed the distance for photos. All down the length of the river, bear tracks in the sand and coarse tawny hair stuck to spruce trees reminded us that other bears were never too far away.

With less than a week remaining on the river we were reminded of the full potential of Arctic weather. Temperatures plunged to below freezing. Wind driven snowflakes as big as loonies (Canadian dollar coins) fell in resounding splats on the tent. Snow accumulated on the tent and on the surrounding hills. It did not feel like July 20. The fleece jackets, toques, and long underwear used for pillow stuffing to this point in the trip were employed for their purposes, and then we scrounged in our packs for more warm clothes.

Jim and Brian paddled 18 miles down the Horton River on a snowy July day above the Arctic Circle. Photo by Maggie Matear.

With no time for a weather delay, we paddled on in the foul weather. Snow changed to ice pellets and stung what little skin we had exposed. In its final distance, the river is surrounded by tall dragon’s teeth hills, steeply eroded conical shapes nearly devoid of vegetation. The clear water of the river became cloudy and tinged with sediment. This too we drank.

With the changing terrain and water quality, we could smell burning sulphur on the wind. Wisps of smoke rose above the hills and diffused into the air as ghost-like apparitions. We were paddling through the Smoking Hills – a distinctive geological phenomenon at the end of the Horton River. The Smoking Hills are the natural result of the spontaneous combustion of magnesium, sulphur, and coal fanned by nearly constant winds off Franklin Bay. Plumes of smoke roiling up the slopes give the hills their name.

A view from the Smoking Hills looking down the coast along Franklin Bay.

A lone bull muskox grazes in the brush along the river.

Walking to the top of the Smoking Hills, we met two musk oxen moving along the ridgeline. Looking like refugees from the last ice age, their long skirts of hair blew in the cold wind coming off Franklin Bay. The big bull telegraphed his annoyance by rubbing his scruffy face on his foreleg. The pair paused long enough for a few photos before charging down the side hill seemingly immune to the steep slope we had just labored up.

On the appointed day, reentry into ‘outside’ life began. The float plane landed on a river the color of tea taken with milk. Our departure from the river threaded a needle of logistical challenges including bad weather and hundreds of miles of air travel in a float plane. In this remote region we felt lucky just to be on time.

Brian Johnston stands on the rim of the third canyon above the Horton River.

Your trip down the Horton will surely be different than what we experienced. It could be better! Here are some things to consider as you plan your trip:

Getting There and Back

Coming from the U.S. or the Provinces, expect to spend two days of travel getting to a float plane base for a flight into the Horton. Our flights took us through Yellowknife, NWT for an overnight stay and then on to Norman Wells, NWT. Similarly, coming off the river at the end, we had overnights in Norman Wells and Yellowknife.

Beginning a trip on the Horton River requires a charter flight from one of: North-Wright Air in Norman Wells (a Twin Otter or Porter on floats); North-Wright Air in Inuvik (a Beaver on floats); or Plummer’s Lodge on Great Bear Lake (a Beaver on floats). Depending on where you start, charter flights will be as long as 300 miles. As mentioned earlier, the most common starting point for the river is Horton Lake. Though, a small lake near the confluence of the Horton and the Whalemen River can be a starting or ending point for a shorter trip.

For those paddling the full length of the river, there is one section of river just before the river delta and Franklin Bay where a Twin Otter or other float plane can land.

Paddling the Horton requires a commitment to either make it half way to the lake at the Whalemen River or all the way to the end of the river for a float plane pickup. Outside of these spots, North-Wright pilots will not make water landings anywhere else. Some travelers have extended this route by continuing on to the Hamlet of Paulatuk, about 60 miles southeast from the end of the river. Scheduled commercial flights out of Paulatuk are a less expensive exit out of the region. Though, paddling on the salt water of Franklin Bay has its own risks and challenges.

The float plane base in Norman Wells, NWT is a busy place during the paddling season. – Photo by Jim Gallagher

Plan Enough Time

We allotted 26 days to paddle from Horton Lake to the end at Franklin Bay. This translates into an average daily mileage rate of 14.4 miles/day. A group that completed the river in a previous year did so in less than 20 days (an average rate of 19 miles/day). Their recommendation was to take more time to enjoy the river. This is well-placed advice. This difference may translate into having enough time to explore, fish, or, instead, having to make miles on the river.

Outfitting Your Trip

Brian and I outfitted our trip with our own gear. Besides the normal array of packs, trail food, stoves, and a tent, we brought a 17 ft. Pakcanoe outfitted with a Cooke Custom Sewing spray cover. We have used Pakcanoes on demanding rivers across the Arctic. Our Pakcanoe performed well on the easy water of the Horton. Edge sectional paddles made by Aqua Bound completed our portable paddling outfit.

If you don’t have the equipment to outfit your own trip or you don’t want the hassle of getting your equipment north, Canoe North Adventures in Norman Wells can fully or partially outfit trips with quality equipment and qualified guides. Canoe North’s whole focus is on outfitting canoe trips and they do it well. They have a close working relationship with North-Wright Aviation where they share a spot at the floatplane base in Norman Wells. It is an efficient operation.

Between the Northern Store and Canoe North, you can find last minute essentials in Norman Wells. We rented bear spray from Canoe North and bought white gas from the Northern Store. Be prepared to pay $30 CD per 4 liter can of white gas. Other grocery items will be similarly higher priced than in communities further south.

A River For Your List

Among the many beautiful rivers in the far north that we’ve paddled, nothing quite prepared us for the beauty of the Horton. Trip reports from other paddlers fall short of describing the experience. Be prepared to meet the demands of this remote river with solid paddling skills, appropriate gear, and a sense of judgement that reflects the isolation of the region.

On a bluebird day in the Arctic, Brian Johnston takes a break in the bow.

Jim Gallagher

Epilogue

In a cool tavern somewhere after completing the Horton River, a ritual post-trip beer turns into two. The barkeep slides another round in front of us. We’ve begun the slow process of shedding the river within us. It will leave us as certainly as we have left the river. What remains are memories of a stunning Arctic river. Eventually we will become, again, part of where we call home. But here in the pub, we contemplate where our next memories will be made. There are miles of other rivers to paddle and other pristine waters to quench our thirst.

Contact us:

Contact us:

Jim Gallagher

Brian Johnston

All photos by Jim Gallagher unless otherwise noted.

Resources:

McCreadie, Mary. 1995. Canoeing Canada’s Northwest Territories, A Paddler’s Guide. Canadian Recreational Canoeing Association.

Canoe North Adventures: http://canoenorthadventures.com; Lin Ward and Al Pace, proprietors.

North-Wright Airways: http://www.north-wrightairways.com