The Bois Brule River: Paddling the Trail of Natives, Fur Traders, and Presidents

TRIP LOG: Submitted by Scott Oeth, February 2016

Paddling the scenic and historic Bois Brule River.

The Bois Brule River in far northwestern Wisconsin is a clear, fast, and rocky river that flows through the beautiful Brule River State Forest as it rushes into Lake Superior. I’d wanted to paddle these waters for quite awhile, and when a weekend opened up recently, I threw the canoes on the roof rack and headed north!

The History of the Bois Brule River

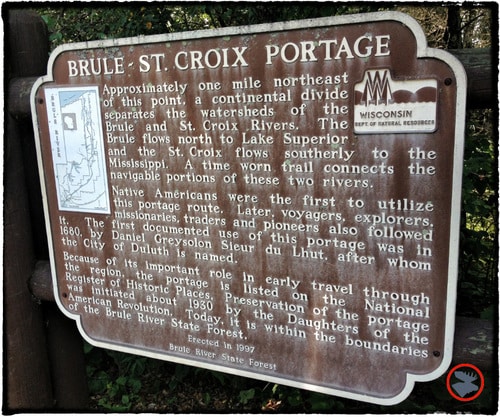

The Bois Brule River (this is the French voyageur translation of the original Ojibwe name meaning “burnt wood”) was formed long ago as an outlet for glacial Lake Superior. When the glaciers retreated, the flow reversed, and springs along the river’s course fed it, causing it to flow north into Lake Superior. The river became a pathway for local natives. During the fur trade era, the Bois Brule was used as a primary travel route; there were large fur trade posts on the Apostle Islands and voyageurs would travel up the Bois Brule, portage two miles to the headwaters of the St. Croix River, then follow the St. Croix to the Mississippi River.

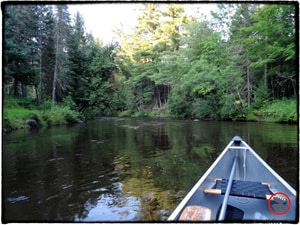

President Coolidge and his river guide, John LaRock, fishing the Bois Brule River. (Photo courtesy of WXPR)

The Brule is also a prime trout steam, and in the 1800s, it became a favorite vacation destination for wealthy families from St. Paul, Duluth, and Milwaukee who sought a northwoods retreat, cool Summer temperatures, and fantastic fishing. Some of those wealthy families included the Ordways and Weyerhausers, who bought land on the river to protect it for it’s natural beauty and for their personal use (the lumber baron Weyerhausers later donated the initial piece of land that became Wisconsin’s Brule River State Forest).

The Bois Brule River was also a favorite of several presidents. Ulysses S. Grant and Grover Cleveland fished the Bois Brule after the Civil War, and then Calvin Coolidge spent the entire Summer of 1928, while in office, fishing the Brule and attending to any unavoidable presidential matters in the local high school library he commandeered for such purposes. Coolidge introduced the Brule to Herbert Hoover and later, Dwight Eisenhower, who also enjoyed fishing the Brule.

The rich and famous wanted to make sure they got their hooks into trout, so a healthy guiding tradition developed on the Bois Brule, as detailed in Lawrence Berube’s book, “The Brule River: A Guide’s Story.” Berube tells some great stories about Coolidge’s native guide, John LaRock, who was regarded as “the undisputed dean of the river men,” and “a master canoe man.” Berube also describes the wood-canvas canoes the guides specially built for fishing the Brule: “They were of beautiful craftsmanship made of natural white cedar with oak ribs and trim. They were mostly 18- to 20-footers. They had built-in live boxes and special low chairs.”

The River: Fast and Slow

The 44-mile Brule has two distinct characteristics: a beautiful and somewhat placid upper section, and a fast, rocky, rapids-filled lower section where the Brule races down to meet Lake Superior. On this particular weekend, we only had one afternoon for the Brule, so we planned to paddle the most action-packed section we could find: the stretch containing Lenroot and May Ledges between Pine Tree Landing and Hwy 13.

“Canoeing the Wild Rivers of Northwestern Wisconsin” includes a spot-on description of the Bois Brule:

“The Brule River downstream from Stones Bridge is one of Wisconsin’s finest canoeing streams. Water levels are extremely uniform on most of the river even after prolonged wet or dry weather. The sand barrens and bog swamps of the upper watershed soak in runoff and discharge a steady base flow. The river itself is remarkably clean and clear until you reach the red clay soils near Lake Superior. The Brule River has a superb series of rapids for the canoeist. In the upper river, rapids are bouncing whitewater slides that are delightful to run with a canoe and yet mostly low hazard. Downriver, the Brule tumbles over the copper range to the old lake plain, the rapids become churning cascades that should be run only by experienced canoeists.” (p. 5)

A Brule is a Brule is a Brule? Not in this case

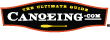

The beautiful and historic Bois Brule River in northwestern Wisconsin.

The beautiful and historic Bois Brule River in northwestern Wisconsin.

Locals call the Bois Brule River simply “The Brule.” However, this northwestern Brule River is not to be confused with the Brule River in northeastern Wisconsin on the border of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, or the wild and challenging Brule River on the north shore of Lake Superior in far northeastern Minnesota. Minnesota’s roaring Brule is difficult to mistake for the Bois Brule River though—especially once you are on the water. Minnesota’s Brule River is so wild that, according to Jim Rada, author of “Northwoods Whitewater,” hardcore whitewater kayakers and play boaters who run it refer to the Bois Brule River as the “Bogus Brule.” Harsh.

Despite Rada’s burn on the Bois Brule, Mike Svob, author of “Paddling Northern Wisconsin,” recommends beginners not travel beyond Pine Tree Landing and rates the May and Lenroot Ledges as “very challenging Class II.” As we would find out, early canoeists were certainly provided plenty of action in traditional open canoes!

Road Trip to the Bois Brule River

Luke’s van, a lifted all-wheel drive Astro cargo van with rugged all-terrain tires, makes a great utility vehicle for the woodsman. Tough, roomy, capable, and affordable, this rig offers great bang for the buck.

Luke’s van, a lifted all-wheel drive Astro cargo van with rugged all-terrain tires, makes a great utility vehicle for the woodsman. Tough, roomy, capable, and affordable, this rig offers great bang for the buck.

Brule, Wisconsin is about three hours north of Minneapolis. Early Saturday morning, my buddy, Silvers, my brother, Luke, and I pointed our wheels north, aimed directly for the Kaffe Stugga in Harris, Minnesota, and dropped the hammer. We like to hunt out local favorites, and I was eager to try this small town diner. Scandinavian roots run deep in Minnesota, and we tore through the diner chow like crazed vikings on a raid! Do not skip the the raspberry pie at the Stugga—really good stuff.

With the excessive Kaffe consumption at the Stugga, we were in need of a pit stop by the time we got to Spooner, Wisconsin. I knew just the place: Big Dick’s Buckhorn Inn! The Buckhorn is everything you want in a northwoods bar: old, dark, and ringed with dozens of mounted walleyes, pike, bear, and deer heads. The Buckhorn has official presidential ties of it’s own: John F. Kennedy stopped at the Buckhorn to have a beer and take a leak while on the campaign trail.

Paddling the Bois Brule River

Despite the sweltering heat of this August weekend, we had more fun paddling the Bois Brule than any president or timber king!

Silvers and Luke were veterans of our recent Quetico trip, but did not have much in the way of whitewater paddling experience. We had a little riverside chalk talk on basic river strategy, safety, signals, and technique, and acknowledged that we could either line or portage the more significant rapids.

I set those guys up in my battle-weary Old Town Tripper. It’s a big, tough, forgiving canoe with a great hull design that can carry a big load, while still offering good maneuverability in rapids. I went solo in my equally abused, but trusty, Wenonah Flambeau. Both canoes are Royalex hulls, a material that slithers over rocks and can handle serious abuse, which was an important attribute given that we are heavy paddlers and the water on the Brule was a bit low, making for a boney run. This river has enough flow from springs to keep it paddle-able throughout the Summer though; in fact, many people talk about paddling the upper section in the Winter when the springs keep it open and flowing.

From the moment we put in, the Brule was fast, challenging, and scenic. Dealing with a muggy 90 degree day, we were already dripping, but the heavily forested river banks and spring waters offered cool relief. I quickly understood why the Brule had become a favorite northern retreat for the old money crowd back in the days before air conditioning.

Lenroot Ledges

After a few miles of twisting and snaking our way through fast riffles and around rocks, we came to the first serious rapids on this section: Lenroot Ledges.

I heard Lenroot long before I saw it. I came swiftly around a bend and saw the river twisting to the left and rushing down a fast chute. I was standing, snubbing my way down the river with the setting pole as I approached the drop. After giving it a quick read, I decided to give it a try while standing.

A word of caution for polers: while the Brule has a wonderful rocky bottom throughout most of its course (and makes for an excellent poling trip), the river bottom just above these ledges is as flat and smooth as a table top—a tough spot to find traction when snubbing with your pole and trying to control your drop into the chute! I worked quickly, jabbing to find purchase, then scraping the tip of the pole in front of my bow, hunting for some feature on the bottom to catch and allow me to position the canoe and slow it’s descent a bit. Luckily, I got my bow lined up with the current and dropped into a crouch as my bow dropped into the frothy tongue of waves. I managed to stay upright while going over my biggest drop since the Machias River in Maine the year before. I eddied out below and just as I grabbed my camera to film the boys as they made their way over Lenroot, they came up sharply against an upstream boulder, broached the canoe, and wiped out. Everyone was in good shape though, and we got the canoe off the rock, emptied her out, and got everyone sorted out.

May Ledges

May Ledges, the most challenging set of rapids on the Bois Brule, were up next. May Ledges is a series of three drops and the last two are sheer drops that stretch from bank to bank.

After a good riverside consult, we decided that at this water level and with our boats, it was going to be tough for two big boys to make it over the drop together. The weight of the first would crater the bow into the rocky bottom as soon as the canoe’s balance point cleared the lip of the ledge. A bit more discussion and I offered to run the Tripper over solo to see how things turned out. I had picked out a notch with decent flow on river right, and despite dragging bottom and leading in slightly off target, I cleared the edge and came out alright. Taking the second canoe through was a piece of cake (check out the video above). The lighter, more nimble Wenonah cruised off the lip and landed with a satisfying splash. After running both canoes through, I was wishing we had more time so I could portage back up and run through May Ledges again!

NOTE: This is a moderately advanced section; it’s not one to try without adequate whitewater experience and gear.

From May Ledges down to our takeout, we enjoyed fast riffles and a wonderfully diverse northern forest edging that ran right up to and overhung the banks of this tight and twisty stream.

Sunday on the St. Croix

On Sunday, Silvers and I decided to finish the weekend with a paddle on the St. Croix River. Another beautiful and historic river, the St. Croix was the second leg the natives and voyagers portaged to on their way from Lake Superior to the Mississippi River. It’s also a designated National Wild and Scenic River and is surrounded by protected land, which makes for a fantastic weekend canoe camping trip—but without the whitewater found downstream on the Bois Brule River. I’ve taken several trips on the St. Croix, and I hope to be back for many more!

Weekend Wilderness

The Bois Brule is a great paddle right in our backyard…well, almost our backyard. The three-hour road trip from the Twin Cities is well worth it for this kind of scenery and near non-stop river fun. It’s a Bull Moose Patrol-endorsed river with two thumbs up! There are calm stretches for the quiet water paddler, as well as the fast water for those who want to shoot the Ledges. I’m looking forward to heading back to the Brule and paddling the entire river—from it’s boggy headwaters all the way to Lake Superior. Next time though, I’ll camp in the Brule State Forest and try my hand at catching a few of the famous Brule trout!

Check out the great video guide from the Morralls, along with other reference material below:

River Trails of Northern Wisconsin by Morrall River Films

The Brule River: A Guide’s Story by Lawrence Berube

Paddling Northern Wisconsin by Mike Svob

Read more at the Bull Moose Patrol blog>