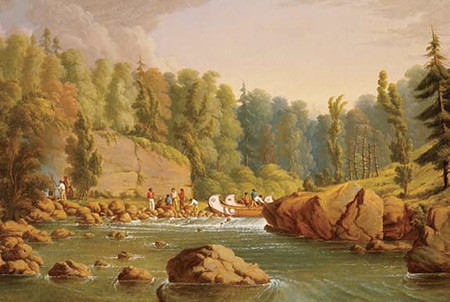

The History of a Painting: The site depicted in “French River Rapids” revealed new insights into Quetico Provincial Park’s fur trade past.

French River Rapids (oil on canvas), 1848-1856; by Paul Kane. Used with permission of the Royal Ontario Museum copyright ROM.

In 2006, Quetico Provincial Park’s French River proved impassable by kayak—so Ken Lister crawled upriver through the slippery, overgrown underbrush. His destination? French River Rapids. As assistant curator of anthropology at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM), Lister suspected that an oil painting of the same name by Canadian artist Paul Kane (1810-1871) portrayed the rapids. If correct, he would disprove widely held notions about the painting’s origins as a river flowing into Georgian Bay, and possibly discover a new understanding of the fur trade. He was, and he did.

In 2006, Quetico Provincial Park’s French River proved impassable by kayak—so Ken Lister crawled upriver through the slippery, overgrown underbrush. His destination? French River Rapids. As assistant curator of anthropology at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM), Lister suspected that an oil painting of the same name by Canadian artist Paul Kane (1810-1871) portrayed the rapids. If correct, he would disprove widely held notions about the painting’s origins as a river flowing into Georgian Bay, and possibly discover a new understanding of the fur trade. He was, and he did.

A Window Into the Fur Trade

Lister’s use of Paul Kane’s art to look back at the fur trade has a sweet sort of synchronicity. Kane was the first Canadian artist to live in and explore the Great Lakes region, even staying at a Hudson’s Bay Company outpost and traveling with voyageurs. Between 1845 and 1848, he produced over 600 pencil on paper, watercolor on paper and oil on paper sketches of Canada’s frontier. They would become the basis from which he later produced over 100 romanticized oil paintings that represented frontier life without being exact replicas of what he saw.

A Toronto exhibition of Kane’s work in 1848 gave many Canadians their first glimpse of the Great Lakes, the Rockies and even Native Americans. In many ways, Lister’s suspicion that Kane’s work could once again shed light on the fur trade returned to the paintings to their original purpose. Yet Lister has always been intrigued by the ability of art to inform anthropology, and he wondered if Kane’s field sketches (unlike his romanticized paintings) were accurate renderings.

“I wanted to know, when we look at a Paul Kane sketch, can we assume we’re looking at what he saw?” said Lister. If the answer was yes, then Kane’s work could be used to identify real-world sites critical to the fur trade. So when Lister arrived at French River Rapids and found that the placement of rocks in the water and a crack in a giant rock wall matched the sketch exactly, it was worth the arduous upriver scramble.

Teasing History from Art and Archeology

As Lister put it, identifying French River Rapids as the site in Kane’s painting “rejoined that particular site with its history.” Kane’s journals and maps indicate that it was used for what anthropologist’s now call a transitory site: voyageurs camped upriver, started paddling at four or five in the morning, and paused at the start of the French River Portage for breakfast. In more recent times, water levels have changed as the result of an upstream dam, and the portage landing has shifted to a different location. The significance of French River Rapids was literally lost to history.

French River Rapids today, photo courtesy Ken Lister.

But with the sketch to point the way, Lister was able to engage Archeological Services Inc (ASI) for a test dig in 2007. Their work revealed a metal hook, a piece of fine china likely European in origin and part of a clay pipe. The hook was of particular interest: Kane’s painting shows voyageurs gathered around a fire, above which a pot hangs from a metal hook and a tripod. The findings were significant enough to warrant a more thorough dig in partnership with Quetico Provincial Park last summer, just in time for the Park’s Centennial. Their efforts were once again fruitful, uncovering glass seed beads, glass tubular beads and the sharpened end of a pole, which might be part of a tripod.

Though small in number, the significance of the artifacts is not. They establish what can be expected at a transitory site, which due to the nature of its use is less likely to produce as much archeological evidence as a campsite. This information can in turn inform future archeological discoveries. But perhaps most significant is the reaffirmation of the understanding that can be gained when art and archeology converge. It’s a type of connection that isn’t often made.

According to Lister, however: “It probably could happen [more] if people were paying attention and asking the right questions.” Or, perhaps, took the time to scramble up slippery riverbanks in search of the past.

Originally printed in Wilderness News Spring 2009 and reprinted with the permission of the Quetico Superior Foundation.

by Alissa Johnson