Paddling into Dead Man’s Canyon, Amistad Reservoir National Recreation Area (Vern Fish).

Submitted by: Vern Fish, 3488 Kingswood Place, Waterloo, Iowa 50701,vernfish@aol.com.

Day 0 – December 31, 2018

It had been a long two day drive from Iowa to Comstock, Texas. We arrived late on New Year’s Eve and settled into the only motel in town. Only restaurant/bar in Comstock, J&P Bar & Grill, had shut down its kitchen at 3:00 PM to enjoy a community pot luck. Rich & Maranda, a husband and wife team, were sound checking their music equipment and preparing to provide the evening’s entertainment. I bought a copy of their CD, Honky Tonk Love Makin’ Night.

The J & P Bar & Grill quickly filled with locals and cheerful guests who have gathered to celebrate and bring in the New Year. The bar keeper says if we buy a beer we can join the festivities and the potluck. Hank and I take turns buying each other Lone Stars. The bar keeper gives me a third Lone Star. Somebody in the room buys Hank and I two tequila shots. I soon begin to feel like a life time resident of SW Texas. Comstock will be remembered as a very welcoming town.

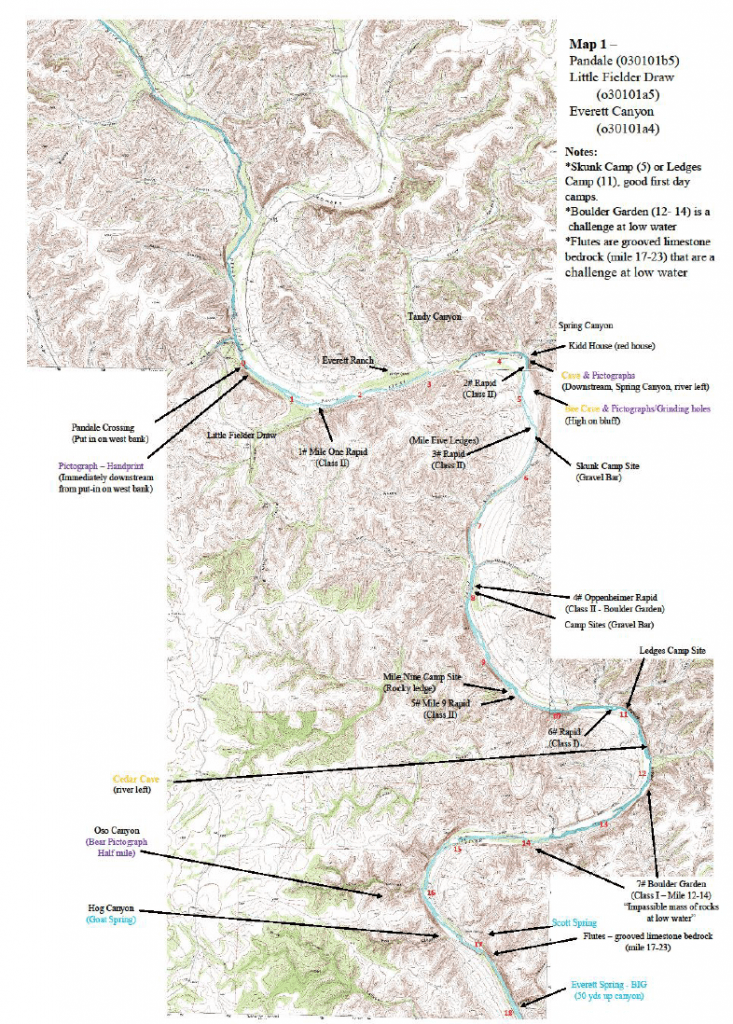

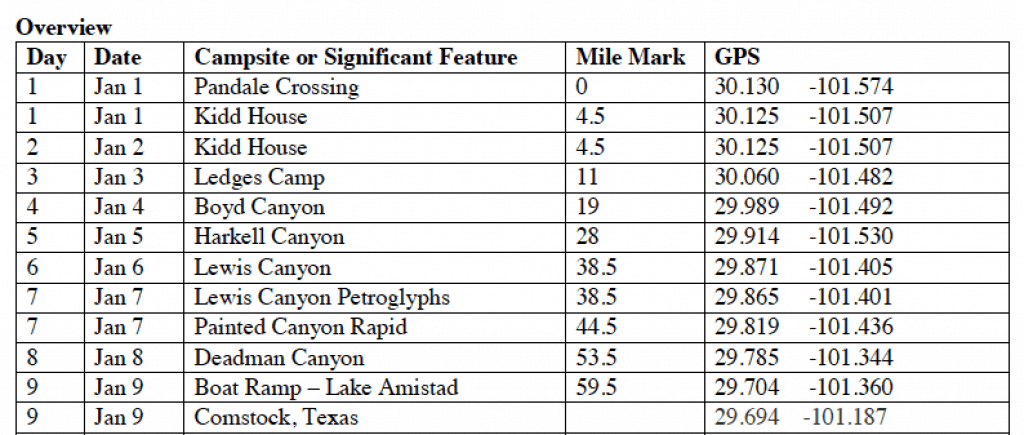

Day 1 – January 1, 2019 (Cloudy and cool, 40 degrees)

At 9:00 A.M. we met our shuttle driver Emilio Hinojosa at his house on the west side of Comstock, Texas. Emilio directs us to drive 60 miles north on Ranch Road 1024 to the small community of Pandale, Texas. With the only store in town being closed, there is not much to see. We follow the gravel road west of town and down to the river. We cross over a low bridge and pull out onto a rock shelf on the river right that serves as a boat ramp.

As we look down river we can see the infamous wall of cane that contours the shore line. This tall non-native invasive plant can now be found along waterways all over the southern USA. It crowds the river bank, blocks the view and is stiff and unforgiving. If you paddle into it, you could be pulled right out of your boat. At best you run the risk of losing your hat.

The ride up to Pandale was both entertaining and informative. Emilio has lived on or near the Pecos River most of his life. He shares several stories about the people who live in the valley and the previous paddlers he’s encountered. Most of his paddling stories do not end well! Broken ribs, busted boats and river levels that are either too high or too low seem to be a constant theme. Emilio’s last words of wisdom are to always have an escape plan in case the river suddenly rises during the night.

Everyone is moving a little slow after the New Year’s Eve celebration at the J & P Bar & Grill and a restless night at the Comstock Motel. No one is in a hurry to get on the river. The sky is cloudy and the air is cool to cold. The river water is a chilly 49 degrees. It does not seem to be a great day to explore the river Emilio loves. At 11:35 AM two canoes slowly slide into the crystal clear water of the Lower Pecos River.

A panoramic view of the Lower Pecos Valley (Hank Ostwald)

A typical cliff face along the Lower Pecos River (Vern Fish).

The river water is too alkaline to drink so the canoes are loaded with two hundred pounds of water housed in four containers. I find sufficient room in my solo boat for two of the big jugs. However, I make the novice mistake of standing the containers up instead of sideways. Within the first mile the current pushes me into a line of cane. I lean and the water jug shifts to the left. Instantly, I find myself standing in a couple feet of fast moving current trying to bail. Welcome to the Lower Pecos River!

I am wet and cold. I bail the water and climb back into the canoe to huddle under my protective spray skirt. Paddling hard I raise my core temperature to an acceptable point. At mile 4.5 the river turns hard right to avoid an imposing cliff wall. Perched on the cliff above the river is the Kidd House. This house has a commanding view of the river valley and is a landmark on the river. The rapid below the house is listed as a “small CII with a tricky drop”.

A typical CI-II rapid, note the cane in the background (Dan Otto).

I follow Hank and Dan down the river. They turn right and disappear behind a thick line of cane. When I clear the corner, I get a glimpse of their green Old Town canoe as it disappears over a ledge. Hank slowly rolls over the right gunnel and into the cold water. I can see him struggling to hang on to his canoe and the paddle.

I jam my solo canoe into a break in the rocky shoreline and grab a rock as the canoe simultaneously swings downstream. I scramble out of my canoe and up onto a rock just in time to see Hank, Dan and their green canoe disappear downstream in a line of foam. As I stand exposed upon this rock the wind unleashes its chill and I feel my core temperature drop. My whole body begins to shiver. I need to get downstream to assist Hank and Dan, but I cannot fathom getting back into the cold water.

I can feel symptoms of hypothermia starting to overtake my body. I am having trouble thinking clearly and my hands are shaking. If I do not do something soon, my ability to function will be compromised. I pop a hard candy into my mouth and scan the water looking for a place to line, portage or run the ledge in front of me. The over grown cane makes it nearly impossible to line or portage on either side of the river. My best bet appears to be a tight little channel on river right. I contemplate the thought of being able to run the drop or jam my boat in between the cane and the rocks in hopes of lining the boat down the run.

My boat is facing upstream so I lumber into the seat and paddle hard into the fast moving current. I pivot left and try to line up on the small opening on the right side. I prepare myself in anticipation of taking on water or another possible dump. I hit my mark, lean back and brace my paddle on the left side. I avoid most of the cane but still take a pretty good slap to the face.

Much to my surprise and relief the canoe slices cleanly between the rocks and the cane with me still sitting in the seat. I am now unquestionably operating on pure adrenaline. I need to locate Hank and Dan and help them get out of the cold water. Around the corner I discover a green canoe floating upside down in a classic capsize position. The spray skirt which holds all of their gear in is also trapping a large bubble of air forcing the canoe to float upside down.

Trying to land a boat in the standing cane (Dan Otto).

I see Hank and Dan have their canoe wedged on the shoreline. I am too damn cold to get back into the water to help them bail. I shout out to see if either of them have hit their head, banged a leg or are bleeding? The major hurdle will be avoiding hypothermia. At some point, I offer them a piece of hard candy that I keep in my pocket. Our next priority is to get everyone quickly changed into dry warm gear.

There is no visible place to stand and bail as their canoe continues to float. The next gravel bar downstream indicates a break in the cane. Hank and Dan float their canoe down river and rest on the gravel bar. I help them pull their canoe up and throw them a bail bucket. The original plan is to reach mile 11 and camp at the Ledges Campsite. In my opinion this is too far considering the sun is setting and the temperature is dropping. I push through the cane and start looking for a suitable campsite.

There is an opening ahead and I see three potential spots where a tent can be pitched. We have a brief conference on the beach and everyone is encouraged to bring their gear in and set up camp. As we unload our travel gear I realize that Hank and Dan are both drenched. I too am cognizant of my own soaked attire.

Dan scouts out an acceptable campsite and starts setting up his tent. I observe Hank’s movements while asking him questions. Hank erects his tent, strips off his wet gear and crawls into his sleeping bag. I toss Hank more hard candies and sarcastically offer to spoon with him to help generate additional body heat. Surprisingly, he declines my offer!

I dig into my “crash bag” and pull out a set of cold weather gear to change into. Dan helps set up the Cooke Tundra Tarp and prepares a meal as the sun disappears behind the shadow engulfed canyon walls. Day 1 on the Lower Pecos has been truly eventful!

The upper section of the Lewis Canyon Rapid (Dan Otto).

Day 2 – January 2, 2019 (Cloudy and cold, <32 – 40 degrees)

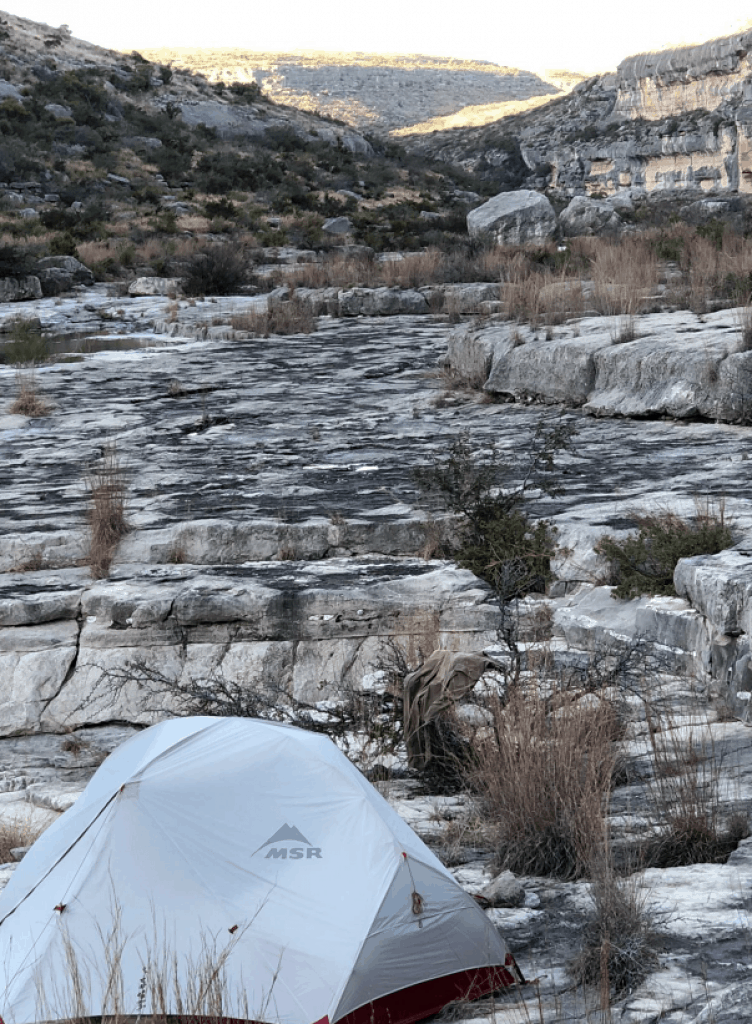

During the night the temperature drops well below freezing. The zipper to my tent has frozen and my damp socks are stiff to the touch. With great difficultly I pull on the partially frozen gear and make my way out of the tent. The ground and tents are covered with a thick white frost. Being from Minnesota, Dan notes how it feels like a fine spring morning.

Everyone is a tad beat up from yesterday’s journey. Dan jammed a thumb and Hank banged his knee. Everyone is cold and the weather report calls for a cold, cloudy day. The group consensus is to stay at camp, eat, rest and try to further dry out the gear. We spend the day hiking up and down the river valley looking for the Bee Cave, a pictograph site. Throughout the day a couple small planes buzz over our campsite.

Day 3 – January 3, 2019 (Clear and sunny, <32 – 66 degrees)

Another hard freeze during the night. We cook pancakes and wait for the sun to clear the canyon wall. Everyone’s MoJo is noticeably down. On our first day we experienced both canoes flipping and the second day was just cold, cloudy and overall depressing. I got a sense that everyone was rightfully concerned about being tangled up in the cane or rolling in another rapid.

It turns out to be a great day to paddle. We play it safe and lined the ledges at Mile 5. The sun is out and we weave through the boulder garden that proceeds Oppenheimer Rapid. Oppenheimer and Mile 9 Rapid pass quickly. There are so many un-named drops that I lose track of where we are on the river. With the warm sun on our shoulders, the joy of padding whitewater has returned. We see our first horse standing in the middle of the river and the day ends at Ledges Camp at mile 11. It was a great day!

A domestic horse standing in the river (Vern Fish).

Day 4 – January 4, 2019 (Warm and sunny, 70 degrees)

The temperature again drops during the night to freezing and there is frost on the spray skirts. The first challenge of the day is the Boulder Field from Mile 12 -14. At low river flows this two mile segment can be challenging to navigate. However, the river is running at 142 CFS so this stretch of the river was not that difficult. There are several blind “cane alleys” that end into whitewater drops. I take water over the spray skirt several times.

The Flutes begins at mile 17. The river bottom is filled with parallel grooves for the next five miles. These grooves are about a canoe width wide. At low water levels a canoe can easily get stuck in a dead end groove and therefore must be lifted into a deeper groove. At 142 CFS this was not a concern for us. At a lower water level this stretch of the river would be almost impassable.

We set up camp at the Boyd Campsite at Mile 19 and search the cliff face looking for a panel of pictographs. A noticeable pictograph panel features two horsemen with stirrups, reins, hats and lances. These images were probably drawn after contact with the Spanish. As the sun disappears behind a canyon wall, a herd of curious horses are seen just off in the distance observing us.

Day 5 – January 5, 2019 (Warm and sunny, 70 degrees)

Another cold night, frost on the tents at daybreak. The sun finally breaks out and off we go into the last segment of the Flutes. This stretch of the canyon is very impressive. The cliffs are predominantly tall and we regularly paddle under their overhangs. Supposedly the Flutes end just after passing a large imposing boulder in the water. The Lower Pecos River is filled with impressive boulders! We do not need a gigantic rock to tell us where the Flutes end.

We fail to find the Piggy Panther pictograph but we do find a place to camp in Harkell Canyon. This is a very large impressive canyon which appears to carry a lot of water when it rains. We camp on the edge of where the water would normally flow. I cannot help but think back to Emilo’s warning of having a “Plan B” in case the river comes up during the night.

The Flutes segment of the Lower Pecos River (Vern Fish).

A hand print on the wall of the Harkell Canyon rock shelter (Vern Fish).

Day 6 – January 6, 2019 (Warm and sunny, 70 degrees)

After breakfast we paddle across the river to look for the Harkell Canyon Rock Shelter. We land on a gravel bar and start working our way up through the cane and brush. The rock shelter is not hard to find. We spend a good amount of time examining and photographing the various petroglyphs.

We find a distinguished handprint at this site. I always get emotional when I observe a pictograph of a handprint. This impression was made by another human spreading red ocher paint on their hand and firmly pressing it against the rock surface. As I stand in front of the handprint, I feel a sensation of traveling through time. I am standing in the same exact footsteps of someone who lived hundreds of years ago.

Immediately after getting back on the water, the river takes us through a couple of CIIs called the Harkell Canyon Rapids. The Pin Rock Rapids come and go with several unnamed CIs both before and after. Along the way we see our first peccary or javelina running along the shore line. A javelin is a medium-sized pig-like hoofed mammal of the family Tayassuidae (New World pigs).

Harkell Canyon campsite (Hank Ostwald)

Somehow we miss the Chinaberry Spring at Mile 34. This was the last place we could replenish our fresh water. Because it has been so cold we have not consumed a lot of water and hopefully have enough water for the next three days.

The only evidence of the man-made Ingram Dam is a couple of posts sticking up out of the water. Still Canyon Rapids is listed as a CII but is easily confused with the dozens of other smaller drops along the way. We paddle by several cultural sites, but only break to observe a few. The canyon is deep and impressive, the river flows around massive boulders that have displaced themselves from the slopes.

The current carries us to Mile 38.5 and Lewis Canyon. We decide to paddle up the canyon to where we find an ideal campsite. The water level is low revealing an exposed small spring. I attempt to locate this spring on my maps, but it is not documented. The spring water is pleasantly warm and justifies a swim. The water is a great relief and very much a contrast to the recent days of very cool temperatures!

The night sky is remarkable. We watch planes, satellites and meteors flash by as the stars circle overhead. In the distance we can hear the rumble of a train which means our trip will soon be over.

Just one example of the many images found at Lewis Canyon Petroglyph site (Dan Otto).

The “Family Portrait” pictograph found in Harkell Canyon rock shelter (Vern Fish).

Day 7 – January 7, 2019 (Warm and sunny, 70 degrees)

We pack up and paddle out of Lewis Canyon and back into the river. The take out point for the walk up to the Lewis Canyon Petroglyph site is just a short ways downstream. This is the first time we hike out of the canyon and we are rewarded with view of the spectacular West Texas scenery. The petroglyphs are equally impressive.

This is the largest known concentration of petroglyphs in Texas and it takes us a while to explore the whole site. I have been to the Jeffers Petroglyph Historical Site in southwest Minnesota but this site is much more concentrated and spreads over a much wider area. Even though I have explored many pictograph and petroglyph sites but most of these symbols are foreign to me.

It is a warm sunny day and the view from the site is captivating. The white clouds are outlined by a cobalt blue sky. The silence from being in the desert is something I savior. You can actually hear blood pulsing in your ears. I walked away from Hank and Dan to enjoy the moment. I think we all hated to leave, but eventually we force ourselves back into the canoes.

The river immediately takes us into the Lewis Canyon Rapids, a CII. Hank and Dan go first and get hung up in the boulder field upstream from the drop. I cautiously follow them in and made it through the majority of the boulders. I miss read the tricky little ledge at the end and roll my boat. Once again, I find myself drenched with water. However, this time the day is sunny and warm and the water feels pretty good! Hank and Dan lined their canoe down the rest of the rapid.

A canoe pinned on a rock on the Dog Leg Right Rapid. It was not one of our canoes! (Vern Fish).

We lined around Waterfall Rapid. This risky CIII is post card pretty but filled with canoe crushing rocks. At the bottom of Dog Leg Right Rapid we spot an Old Town canoe pinned against a rock with a life jacket still attached. This canoe is a recent victim of the river because the life jacket has not yet been ripped away. Three Rock Rapid, Long Chute Rapid and several small rapids fly by as the river continues its voyage to the confluence with the Rio Grande River.

In the distance we could hear the Painted Canyon Rapid. This CIII-IV rapid is the biggest stretch of whitewater on the Lower Pecos. Getting off the water on river right was a difficult climb up a rock face. The ledge along river right has plenty of room for camping so we set up camp.

Dragging a canoe through the Flutes section, Mile 17-23 (Vern Fish).

Panoramic view of the Painted Canyon Rapid (Hank Ostwald)

Day 8 – January 8, 2019 (Warm and sunny, 70 degrees)

We spend most of the morning eating breakfast and portaging around Painted Canyon Rapid. It is tough getting the canoes up and on to the ledge. It is even harder to get them back into the water. The portage ends with a five foot drop into eddy. We lower the gear and lined the canoes into the water.

The next couple of drops are fun but the Weir Dam at Mile 46 is a unique experience. At high water this dam could be a hydrologic death trap. At 140 CFS we just pull up and drag our canoes over on river left. The Weir Dam Rapid is just downstream on river right but it is a blind entry because of the cane. You can hear the water roaring but you cannot see the feature.

You cannot scout the rapid and you must enter by paddling down a cane alley. Hank and Dan disappear into the cane. I wait a while and then intuitively follow. Their canoe gets hung up at the top of the rapid and they direct me to go left and hook right. A couple of tight turns, a glancing blow off a rock and I emerge from the foaming water with a wet spray skirt but upright. I have learned to respect the Lower Pecos River.

The map show three CII runs from Mile 47 to 49 including Big Rock Rapid. At our water level none of these features are very difficult. From Mile 49 to 51 the river is filled with big rocks. I call them “Desert Icebergs” and they create a paddling maze. At high water levels this maze would be very challenging.

We canoe by the Pass Through Cave on the way to Dead Man’s Canyon. A large cave goes through the canyon wall on river right and exits near the mouth of the side canyon. Paddling into Dead Man’s Canyon is memorable. A high, vertical cliff comes out of the water on canyon left. It is possible to paddle under some of the overhangs on the way to the grassy campsite on canyon right.

Avoiding another “Desert Iceberg” near mile 50 (Vern Fish).

Day 10 – January 10, 2019 (Warm and sunny, 60 degrees)

The weather report calls for a sunny day with light winds out of the north. The wind is scheduled to switch directions and come out of the south the next day. At this point there is no current because we are paddling into the flat waters of the Amistad Reservoir. Thus, we are motivated to get off the water before we are forced to paddle into a head wind.

As we round the first curve we can see Pecos High Bridge which serves the Southern Pacific Railroad. This is the highest railroad bridge in Texas. This is the source of the train horn that we’ve been hearing for the past three days. On river left we can see the Railroad Pictographs from the river. These images are really large!

Three miles later we approach our take out point, a boat ramp that serves the Amistad Reservoir.

Trip Planning

If you are planning a trip on the Lower Pecos River start by reading the trip guide written by Louis Aulbach and Jack Richardson, The Lower Pecos River. This is a well written guide that provides a detailed outline for planning your trip. In today’s digital age you may be able to find a copy online. You can also try to order this guide directly from Louis Aulbach.

Louis Aulbach

P.O. Box 925765

Houston, Tx 77292-5765

There are many trip reports that provide insight to paddling this river. The following were easy to find and were helpful:

https://community.nrs.com/duct-tape/2016/08/12/return-to-the-pecos/

https://www.outsideonline.com/1818766/lost-river-divine-reincarnation

http://www.texasescapes.com/TexasRivers/PecosRiver/Canoe/CanoeingPecosRiver.htm

Finding a shuttle driver is your next challenge. We used Emilio Hinojosa who lives a mile west of Comstock, Texas. He shuttled us to the Pandale crossing for $175 and left our vehicle at the Amistad Reservoir boat ramp under I-90 high bridge. Emilio Hinojosa Emilio’s Charter Service P.O. Box 733 Comstock, Texas 78837 830-317-0760 (c) In case of an emergency Emilio recommended that we call the US Border Patrol. They are the only agency that has complete access to the river. Their number is 432-292-4600 There is one motel in Comstock (432-292-4484) and the only restaurant J and P Bar & Grill (432-292-4338), is located across the street. The only gas station/convenience store is also located across the street from Comstock Motel.

Download a PDF version of the Trip Report with Maps