A Thin Blue Line on the Map

Trail Creek! This was the day. For years (off and on, but literally years) we had looked suspiciously at the thin blue line on the map linking Trail Lake with the Maligne River. Had people been there before? Undoubtedly. How many? Inquiries suggested very few. Would the creek be passable? Today, we would find out.

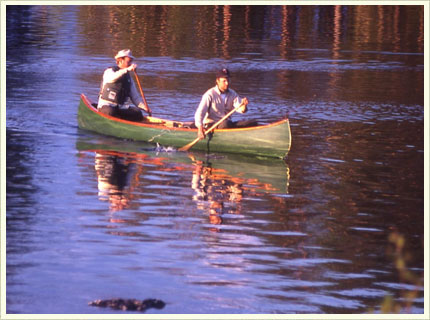

It was Roger and Larry’s idea, get together some friends—Boy Scout guides who had worked at the Charles L. Sommer Wilderness Canoe Base—and go to extra-adventurous places in the Quetico. They had recruited me and Don, decades-old friends and fellow “Charlie Guides” as well as Roger’s dog, Thor (another Quetico veteran). The trip so far had taken us from Moose Lake, in the middle of the Boundary Waters, northwest to Quetico Lake where we turned south to start our serpentine route back. We were camped on Your Lake on a lovely point apparently inhabited by a most obnoxious bird making noises perfect for the Jurassic Park soundtrack all night. Breaking camp early, we loaded our Seliga canoes and headed for the end of the eastern lake.

For those that aren’t familiar with Joe Seliga, he has been making wood/canvas canoes in Ely since 1938. The Art of the Canoe with Joe Seliga, which documents Joe’s life and craft, was named Northeastern Minnesota Nonfiction Book of the Year in 2002. In 1993, when Roger went to pick up his new Seliga, Larry had gone along and put his name on the years-long waiting list. Now both their forest-green, mahogany-trimmed canoes glided along on the smooth lake under overcast skies, but with an important difference. We had been switching paddling partners every other day and bow or stern positions at lunch. I had paddled in Roger’s canoe the first two day, then with Larry. Now, on the fifth day, in order to continue the pattern, Don and I were paddling Larry’s canoe. Paddling it towards what might be a narrow, rock garden full of twists and turns as well as sharp branches reaching out to remove paint from our hull (well, Larry’s hull). He watched us carefully while traveling with Roger. A major reason for arriving here on the first of June was our hope that there would be enough water to at least float a loon (and to be there before the mosquitoes were out in force). Of course, we were always careful not to damage our canoes, because they were our precious lifelines, because of their beauty, and because we didn’t want to be driving back through Ely and have Joe see scratches on one of his creations.

We portaged to Snow, then Little Pine Lake. Thor helped make single tripping possible by carrying his supply of dog food. There, off to the right in a dead tree was a bald eagle. Checking the map, we saw that the eagle was between us and the creek; we’d be able to get a good look at it without wandering out of our way. As we drew near, it took off, toward the creek and around a bend. Paddling on, the waterway narrowed. There, ahead was the eagle. Was it leading us on as a spirit guide or were we just chasing him along his little valley?

Beavers be here. Trail Creek widened as we approached our first dam. There wasn’t a whole lot of difference between the water levels on each side, so the four of us were able to lift the canoes over. Thor supervised. Another bend and the creek became a trickle through a wide gravel bed. Time to portage, but there was no path so we just walked down the stream, wet-footing has always been our style anyway. Paddle to the next dam. Once more, the eagle appeared and flew downstream. Most times, we had to unload our packs from the canoe before lifting them over the dam. No scratches that time. Careful. Repeat.

On the left, there were some ruins from a logging operation. The book, Quetico Provincial Park: An Illustrated History, indicates that this area was logged about 1936, a summer of big fires followed by one of the last (and one of the biggest) winters of red and white pine harvest. The book shows logs being transported between Trail Lake to March Lake, but doesn’t say which direction. I wondered if the logs were going out through Trail Creek or east through Bent Pine Creek and into Sturgeon. On other trips, I noticed extensive logging artifacts on Bent Pine. Either way, the logs would go down the Maligne River to Lac la Croix. Maybe they tried the more direct route through Trail Creek and gave up? I wouldn’t have blamed them.

OWWW! A branch on a beaver log got poked into the side of Roger’s canoe. Fabric ripped. At least it was above the water line. Hoisting Larry’s canoe, I slipped but recovered in time. Putting a pack on my back, balancing on a bark-stripped stick, I turtled. As my feet flew skyward, the pack softened the landing. The water slowed the fall too, and the logs at the base of the dam had some give to them. Thor supervised. Between six and 20,000,000 dams later, we felt we must be near the end (OK, closer to six). We gazed over the next dam to find. . .mud. A dam downstream must have gone out. No spirit guide; we were on our own. The left bank had more open meadow, so onto our shoulders went the packs and canoes for the final stretch to the Maligne River. Four hours of toil, a bit over four miles (not counting zig-zags); we had survived Trail Creek. Without our buddies, the beavers, there would have never been enough water to make it. Time for lunch. Hudson Bay Bread (a high-energy oatmeal bar) was slathered with peanut butter around the edges to keep the jelly from falling off; calories flowed into our bodies. While Roger duct-taped the six inch tear in his canvas, Larry thanked Don and me for taking care of his canoe.

On the Maligne, just upstream from us, was Tanner Lake. John Tanner, stolen

as a young boy in Kentucky to take the place of a Shawnee mother’s dead son, he became famous by his Indian name White Falcon. John was shot and left for dead on “his” lake, because of a dispute on whether his daughters should attend a white school. He was rescued by passing Voyageurs. Moving back and forth between white and Indian society was not easy for him. In 1830 he published A Narrative of the Captivity and Adventures of John Tanner during Thirty Years Residence Among the Indians which gives us a valuable look at native societies of that era. Tanner disappeared forever after being accused of murder in 1846.

Loading the canoes, we moved downstream on the Maligne; it was difficult to tell where Trail Creek came out. I wondered if Tanner had noticed it. Meeting the Darky River we turned south–upstream–then did multiple small portages up the river to Minn Lake. Camping on an island, nobody had the energy to go out fishing that night; instead, cribbage with Larry’s travel sized cards and board. Roger and Thor turned in early. Then the clouds broke open in the west revealing a spectacular orange and purple sunset. Neither our ooohs and aaahs nor camera shutters clicking could draw Roger and Thor from their tent. Too bad.

The rest of the trip was also a pleasure as we traveled through McAree, Argo, Ted, McIntyre, Cecil, Kett, and Basswood before ending at Fall Lake, near Ely. So what makes me look back on this day so fondly? A bit of everything! New territory, a challenge completed, the wildlife, good company, the Seligas. We would have traveled over those beaver dams faster if we had used aluminum or even kelvar canoes. But while protecting the canvas, we were more aware of our surroundings, paying attention to every rock and stick. Imagine what it would be like to paddle (and portage) a birch bark canoe through such a maze.

Would I go back again? Only early in the year, before the mosquito hatch. I’d prefer to try Wildgoose Creek (new territory and rumors of brook trout). Hopefully, it will make a good story.

Copyright © 2008

Chuck Rose