Ottertooth River Trip Report

Trip Dates: July 1 – 11, 2018

Nearest City: Armstrong, Ontario

Put in: Sparkling Lake

Take out: Obonga Lake

Distance: 56.78 miles

Water level: Low

Boat: Northwind by Bell Canoe Works (16’6’’ Royalex)

Outfitter: Mattice Lake Outfitters (www.walleye.ca)

Paddlers: Dave Fish, Winsor Heights, Iowa

Vern Fish, Waterloo, Iowa

Difficulty: Challenging – Because of the severe topography, low water, lack of campsites and non-existent portages, this trip was a physical challenge.

Submitted by: Vern Fish, vernfish@aol.com

Obonga/Ottertooth Provincial Park

“The park offers challenging, and remote canoeing opportunities. The route, which passes through Ottertooth Creek canyon, presents the canoeist with severe travel obstacles and minimal campsites. However, one is rewarded with unusual and spectacular scenery of rapids, waterfalls, talus boulders and steep canyons. Few people travel this area.” Park management plan (https://www.ontario.ca/page/obonga-ottertooth-provincial-park-management-statement)

I was “encouraged” to paddle the Ottertooth by Phil Cotton, the founder of the Friends of Wabakimi. The Ottertooth canoe route forms the southern boundary of the Wabakimi Area. The Wabakimi Area includes over 6 million acres of Crown land that embraces Wabakimi and several other provincial parks and conservation areas. The Friends of Wabakimi was created to rehabilitate and document historic canoe routes in the Wabakimi Area. The Ottertooth is one of the last waterways in the Wabakimi Area to be surveyed and documented by the Friends of Wabakimi.

In 1784 Ed Umfreville was hired by the North West Company to find a canoe route that would by-pass the Grand Portage route across Northern Minnesota. Under the 1783 Treaty of Paris, the Grand Portage route became the property of the Americans. Umfreville avoided the Grand Portage route by paddling from Lake Nipigon to Winnipeg by going up the Ottertooth drainage to the height-of-land and then down the Kashishibog River.

Phil Cotton wanted someone to explore and document this historic waterway. The management plan points out that there are two undocumented pictograph sties in the Ottertooth Creek system. Thus, the purpose of this trip was threefold. Document the status of Ottertooth canoe route, try to find evidence of the 1784 route pioneered by Umfreville and find the pictograph sites.

A quick internet search found almost no information on the Obongo/Ottertooth Provincial Park. I found references to a government document called Graham Area Canoe Route # 9. However, this document was no longer in print and no longer available. Phil Cotton had a copy Route # 9 that he shared with me. He also provided a link to an abridged extract of Umfreville’s 1784 journal complete with modern maps edited by Bill Martin of Thunder Bay, Ontario. The following is a link to that that that journal extract: http://freepages.rootsweb.com/~wjmartin/genealogy/nipigon.htm

Maps & References

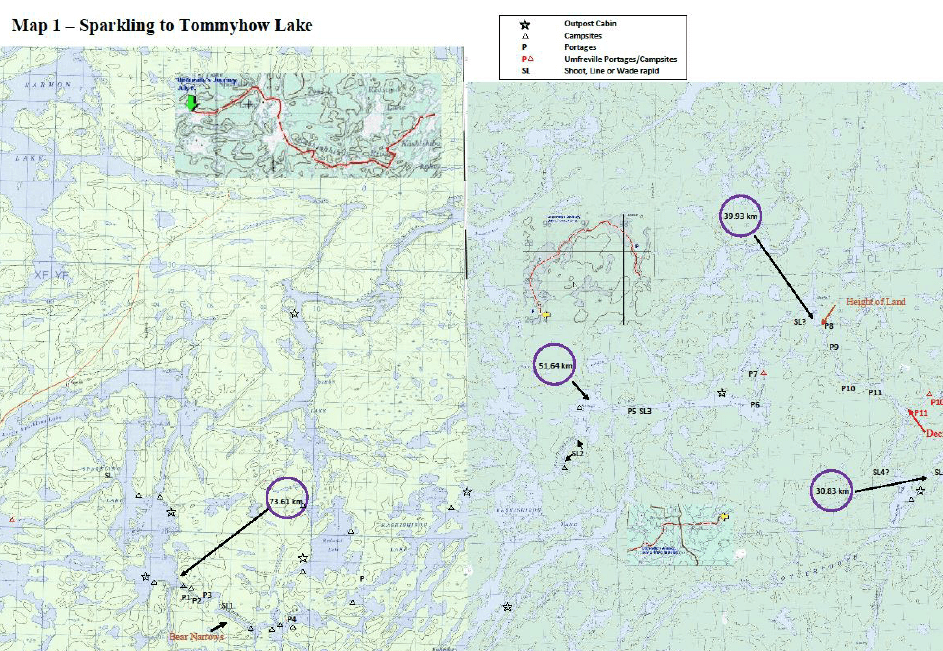

The Friends of Wabakimi provides a planning map for the entire Wabakimi Area. Backroad Mapbooks (www.backroadmapbooks.com) provides a 1:100,000 scale map of the Obonga/Otttertooth Provincial Park. I used both of these maps to start my planning process. I ordered the following 1:50,000 digital maps from YellowMaps (www.canmaps.com):

52 H/13 Uneven Lake

52 G/16 Harmon Lake

52 H/14 Gull Bay

I “digitally” joined these maps and reduced them down so they would fit into 13” X 17” a SealLine map case. I then transferred the details and notes from the Graham Area Canoe Route # 9 brochure, the Backroad planning map, Umfreville’s 1784 journal and the park management plan on to these maps. I laminated the final version of these maps for the trip.

We also used the Redsand Lake to Brightsand River map from Volume Five of the Wabakimi Canoe Route Maps. This map provides detail for the paddle across Kashishibog Lake. Volume Five has been produced by the Friends of Wabakimi. Wabakimimaps.com offers a map called Kopka River 5 that shows where Graham Road intersects the Kashishibog River and provides vehicle access to Sparkling Lake. If we had wanted to drive to this put in point, this map would have been useful.

Permits & Fees

Permits & Fees

We purchased non-resident daily camping permits for Crown Land from Mattice Lake Outfitters. Non-residents can buy camping permits online (www.ontario.ca) or through participating Service Ontario Centres. The cost was $9.35 + tax (per person, per night).

Logistics

Dave Fish, my first cousin, drove from Des Moines to my house in Waterloo, Iowa. We stopped north of the Twin Cities and completed the drive to Armstrong, Ontario the next day. We spent the night in a cabin provided by Mattice Lake Outfitters (www.walleye.ca). On Canada Day, July 1, our canoe was lashed on to red DeHavilland Beaver and we were flown to Sparkling Lake. We unloaded, got our bearings and started paddling up the Kashishibog River.

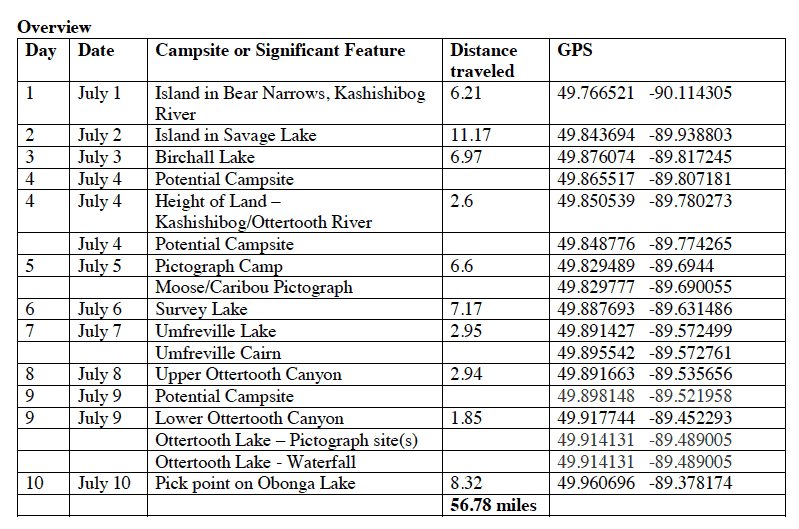

The original plan was to paddle up the Kashishibog River and cross the height of land into Ottertooth Creek. We were going to follow the Ottertooth down to Obonga Lake and then work our way back to Lake Mattice where we started. I had included a side trip up Survey Creek to follow the Umfreville’s 1784 route. I estimated that we could do this in 10 days. Crossing the height of land and working our way down the Ottertooth Canyon proved to be very difficult and time consuming. It actually took us 10 days just to get to Obonga Lake. The following is an overview of where we camped and how far we traveled each day.

Highlights & Observations

Highlights & Observations

The park management plan said that this route presents severe travel obstacles but offers a spectacular scenery. I would agree. The four portages across the height of land between the Kashishibog and Ottertooth River only covered about 2.6 miles but it took a full day. Three of the portage trails had disappeared in a burn area that had been repopulated with young jack pines. According to Umfreville, the second portage (portage de Savanne) was “450 yards and road was mostly swampy”. The last portage (des Grosses Roches) was 430 yards of “bad road over sharp rocks”. Neither of these portages had changed since 1784.

The portage into Ottertooth Canyon took almost 6 hours to find, clear and cross. This portage drops 200 feet and is 650 yards long. In places the trail was too steep to carry the canoe so we lined it up and down the rock face. We did find blazes on trees and that someone had recently marked the trail with survey tape. However, we had to clear a path through the bush.

When we finally got back on the water the sun was disappearing behind the canyon walls. Our maps did not show any campsites so we were frantically searching the vertical walls for a place to camp. Tucked into a low spot just before the next set of rapids was a seldom used site with barely enough space for two tents. We watched the sunset dance across the canyon walls as we set up our camp in complete exhaustion.

The second day in the canyon took almost 12 hours of continuous paddling, wading, portaging, lifting, lowering and lining to go 1.85 miles. We spent over two hours cutting logs, wading and lining down a half mile of rapids. The portage around a roaring waterfall was enchanting but watching the river disappear under the rocks was surreal. At one point we had to tight rope the canoe and gear across a log jam bridge. Again, we faced fading daylight as we struggled to find a semi-flat slab of rocks for our tents.

The second day in the canyon took almost 12 hours of continuous paddling, wading, portaging, lifting, lowering and lining to go 1.85 miles. We spent over two hours cutting logs, wading and lining down a half mile of rapids. The portage around a roaring waterfall was enchanting but watching the river disappear under the rocks was surreal. At one point we had to tight rope the canoe and gear across a log jam bridge. Again, we faced fading daylight as we struggled to find a semi-flat slab of rocks for our tents.

Portaging out of the canyon and into Ottertooth Lake on the third day was bitter-sweet. The canyon was picturesque and technically challenging. Each barrier was a unique physical challenge to overcome. However, we were both tired and beat up. I was concerned that one of us was going to get hurt before we got out. The lake was equally stunning and it was an easy paddle.

As our beat up little canoe glided across Ottertooth Lake we could hear but not see the first waterfall coming into the lake from the west. Umfreville had portaged up and around this waterfall in 1784. We could see but not hear the second waterfall which marked the location of the two pictograph sites on the north shore. Water flowing over the vertical wall of black rock was a highlight of the trip. Spending three days and two nights in the Ottertooth Canyon and on Ottertooth Lake was well worth the trip.

Along the route we paddled by one active outpost cabin and visited four abandoned or underutilized cabins. We saw six otters, a few eagles but no moose or wolves. We caught enough walleye for three meals. We also ran, waded, lin ed or portaged dozens of small rapids and a couple of waterfalls. The last twisting CII rapid ended in a massive log jam which we had to climb over to get into Obonga Lake.

Along the route we paddled by one active outpost cabin and visited four abandoned or underutilized cabins. We saw six otters, a few eagles but no moose or wolves. We caught enough walleye for three meals. We also ran, waded, lin ed or portaged dozens of small rapids and a couple of waterfalls. The last twisting CII rapid ended in a massive log jam which we had to climb over to get into Obonga Lake.

The park management made reference to two pictographs within the Ottertooth Canyon. The Graham Area Canoe Route # 9 brochure canyon encouraged paddlers to look for an excellent likeness of a moose pictograph 3.5 miles east of Tommyhow Lake. We found a pictograph east of Tommyhow Lake but to me it looked more like a bull caribou then a moose. On the last day we found two pictograph sites on the north shore of Ottertooth Lake. We did not see any pictographs within Ottertooth Canyon. Finding several legible pictographs at three different sites was one of the goals for the trip.

Another goal was to retrace a part of Edward Umfreville route. We portaged or ran many of same rapids he crossed. His 1784 descriptions of these trails and waterways were still accurate. However, today many of these portages have been burned over and are not being used or maintained. We visited two of his campsites but neither being used by contemporary paddlers. We did leave a cairn on one of his campsites on an unnamed lake. I have taken the liberty of naming this lake Umfreville Lake. Because of time restraints and fatigue we did not paddle up Survey Creek or explore the 2.5 mile portage Umfreville took to avoid the Ottertooth Canyon.

Another goal was to retrace a part of Edward Umfreville route. We portaged or ran many of same rapids he crossed. His 1784 descriptions of these trails and waterways were still accurate. However, today many of these portages have been burned over and are not being used or maintained. We visited two of his campsites but neither being used by contemporary paddlers. We did leave a cairn on one of his campsites on an unnamed lake. I have taken the liberty of naming this lake Umfreville Lake. Because of time restraints and fatigue we did not paddle up Survey Creek or explore the 2.5 mile portage Umfreville took to avoid the Ottertooth Canyon.

The main purpose of the trip was to document the route for the Friends of Wabakimi. A day by day trip log and more photographs from the trip are provided in a separate document. The trip log provides a detailed summary of the route with descriptions and locations of campsites, rapids, and portages. We also measured or estimated the lengths of the portages we crossed.

Trip Summary

Our experience reflects what was stated in the park management plan. This route is rarely traveled and presents the paddler with severe travel obstacles and minimal places to camp. The portages have disappeared into the forest and are physically challenging. However, Ottertooth Canyon is spectacular and Ottertooth Lake is magical. The Canyon reminded me of hiking through the side canyons of Lake Powell. Hopefully this trip report will prepare the adventuresome paddler to tackle this remote wilderness.

Historical Note

It should be noted that Umfreville’s journey from the mouth of Nipigon River to the confluence of the English and Winnipeg Rivers by way of Lake Nipigon was 286 leagues with 72 portages. The Grand Portage route is a distance of 214 leagues with only 26 carries. The Lake Nipigon route was only suitable for the small canoe, canoe du leger, and not the larger canot du nord. The North West Company continued to retain its headquarters at Grand Portage for 17 years after Umfreville’s journey.

All photos courtesy Vern Fish.

Download a PDF version of the Ottertooth River Trip Report with Route Details and Maps