Summer at 69° North Latitude

Brian and Jim on Wellington Bay. Photo by Brian Johnston.

At 69° North Latitude in the Canadian Arctic, the summer of 2014 seemed to have taken a vacation. Elsewhere on the globe, this year shaped up to be the warmest in 134 years of recorded weather history. On Victoria Island in Nunavut, the warmth experienced elsewhere on the planet was elusive. In July the residents of the Arctic hamlet of Cambridge Bay could not remember a year when so much ice remained on inland lakes and the saltwater bays of the island they call home.

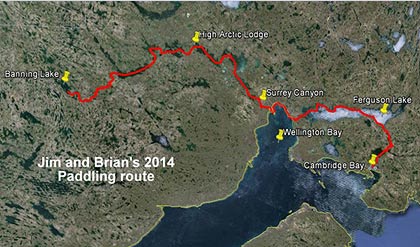

In 2013, my paddling partner Brian Johnston and I paddled the Nanook and Kuujjua Rivers on Victoria Island. The summer of 2014 we planned to paddle the Banning and Surrey Rivers further south on the island. Connecting a maze of waterways, we would take a leisurely month to paddle a 200 mile route back to Cambridge Bay. Following the lure of new territory, we’d paddle an undocumented route near the northern edge where navigable rivers occur.

We arrived in Cambridge Bay a bit surprised to see ice covering the bay and freshwater lakes. The good news was that all eight checked bags containing our gear arrived with us. One duffle bag contained our 17 ft. folding PakCanoe.

Bill the pilot operated the one and only floatplane on Victoria Island in early July. Two other floatplanes were expected that week, but both remained south for unexpected repairs. Bill was flying load after load of supplies into High Arctic Lodge where he worked. In an observation of ultimate practicality, Bill said it didn’t matter if we were ready to go or not – lakes all along our route were still mostly frozen.

While waiting for an opening on the flight schedule and for more open water, Brian and I enjoyed the sights of Cambridge Bay. We rode bicycles out to the wreck of Roald Amundson’s wooden ship, the Maud, and walked among the walls of a stone church built in 1954. We stopped in at the Arctic Coast Visitor Center and learned more about the people and history of the area. The Center features unique Inuit cultural objects and historical photos. A traditional skin-on-frame kayak hangs on the wall above the front desk. Along the wall is a very large soapstone and whale bone sculpture by the late Gjoa Haven carver Judas Ullulaq. A full size polar bear mount stands in the corner and towered over us. The white bear was a good reminder that we may not be at the top of the food chain during our visit to the island.

Nunavut Day harpoon competition, photo by Jim Gallagher.

Nunavut Day bannock frying, photo by Jim Gallagher.

On Nunavut Day we strolled up to the community celebration to share some food and watch traditional skills competitions. In a ball field we watched a harpoon throwing competition. Nearby a line of older women each with their own camp fire tested their skill and speed at frying bannock. Mixing easily with the good humored residents, we enjoyed the high drama of competitive bannock frying while sipping a cup of fire-brewed tea.

Our revelry was broken when the local expediter for the air charter company tracked us down. Bill would fly us to our destination later that afternoon. We returned to our home base and began the hurry scurry of packing our gear for the flight out. As we loaded the floatplane, we talked with Bill about our planned route down the Banning and Surrey Rivers. He seemed a bit dubious and offered that we would be paddling a lot of shore leads because of the widespread ice along our route. During the hour-long flight to Banning Lake I looked down at the mottled brown and white landscape several thousand feet below. The white of still frozen water transected the land into a tundra mosaic. Any flowing water below was not obvious. I tamped down creeping doubts about actually being able to paddle this summer. Perhaps ice skates would be more appropriate.

What was not obvious at several thousand feet came into focus as Bill descended and circled the Cessna above Banning Lake. The lake was still mostly ice covered, but there was enough open water at the river exit to land the plane and begin our route downstream. We were arriving right on the cusp of the open water season.

For me the real start of a canoe journey begins when the floatplane does a fly-by and tips its wings in a final good bye. I was left with the sounds and pungent smells of the tundra. The skittering call of a sandhill crane filled the heath-infused air. I look at our mound of packs and wonder if we forgot anything important. The seemingly unlikely convergence of months of planning, thousands of miles of travel, and just enough open water makes me feel that we are lucky to be here at all.

The next morning we transformed the large black duffle bag of aluminum poles and vinyl/rubber skin into a 17 foot canoe. This sturdy craft is not too much different in concept than the skin-on-frame kayaks and boats once used by Arctic people in generations past. Each craft is propelled by flat-bladed paddles – plastic and carbon fiber for ours and the traditional craft with spruce blades from the tree line many miles to the south.

Jim Gallagher wading through ice on the Banning River, photo by Brian Johnston.

Over the next week we found our rhythm of travel. We got reacquainted with daily routines and paddling muscles. The labyrinth of ice on most lakes tested our ability to pick viable paddling routes. Our pace was slow enough to allow exploration, to walk along the top of interesting hills, and to fish below riffles. Herds of muskox were tolerant as we took their photos. One herd on an island grew overnight after a cow gave birth to a rare mid-July calf. Fitting our tent among rock tent rings and kayak stands, ancient Inuit campsites became our own for the night. Good campsites remain good ones even after thousands of years.

At an esker campsite I watched lake trout cruising near shore. Their dark shapes moved lazily, basking in the warmth of the shallow water. Candling ice floated in a mass a few hundred yards offshore. Casting a spoon out into the shallows I caught one fat trout after another. Each seemed surprised at being reeled in and splashed indignantly when I released them. I marveled at their strength and wildness as they slid from my hands in the water.

Arctic weather flexed its muscles as strong winds and rain kept us tent-bound for nearly three days. Periodic forays to the outside required full rain gear. Reading, journal writing, and sipping hot drinks filled those days. We learned later, after the trip, that nobody moved during that storm. Planes were grounded and people stayed inside all across Victoria Island.

More than a week into our trip we stopped at High Arctic Lodge along the Surrey River. The lodge hosts Arctic char anglers and muskox hunters during its short two month operating season. One of the owners, Dawn Berry, greeted us as we landed our canoe. Before long she was making hot drinks for us in the lodge. The camp cook slid plates of fresh baked bars and cookies onto the table for us. Dawn invited us to stay and share the turkey roasting in the oven. I was wilting in the warmth of the lodge and suffering from a form of social anxiety unique to wilderness travelers. The sudden onslaught of friendly faces and new names tested my memory. The heat and the knowledge that I hadn’t bathed in more than a week made me long for the open air beyond the lodge. Rather than interrupt our traveling routine, we paddled on. Dawn sent us on our way well provisioned with cookies, jerky, and a few welcomed cans of beer.

In the final few miles of the Surrey River the river drops 20 feet per mile into the sea. Canyon walls rise up from the river. We threaded a tenuous paddling route through the ledges and rapids in the canyon and managed to avoid a mile-long portage. I remember the raw power of the river and the smallest of safe passages for our canoe – the canyon wall rising off my right shoulder and the river falling over a ledge to my left. Fast and very cold water swept through the chasm, day and night, unceasingly, in a final rush into Wellington Bay of the Beaufort Sea.

Jim and Brian, Surrey Canyon, photo by Brian Johnston.

While paddling the saltwater of Wellington Bay we met three Inuit men at their camp. They had been tending fishing nets set for arctic char on the bay. Inside a canvas wall tent Jack, Nathan, and Brent shared some hot drinks and enjoyed the unexpected company of two strangers arriving by “kayak”. Historic family ties to this fishing spot gave each a portion of a commercial fishing quota. The fishermen sent us on our way with a fish from their catch and some tips on where to get fresh water along our route.

In a region where canoe travelers are uncommon, I noticed a common theme whenever we met people along our route. We were given things all travelers hope for: shelter, refreshments, food, and information to help us along our way. Passing planes tipped their wings if they saw us below. We were traveling across their home territory and they seemed to have a vested interest in our success and safety.

Pans of ice on Wellington Bay chilled the salt air. We wove a crooked course through the maze of ice. Fog rolled in off the bay and soon our vision was limited to a few yards. Keeping land on our left when we could see it, we crept forward in thick gray fog. When the land disappeared in the fog, only our GPS could confirm our location on the bay. Curious seals spy-hopped out of the water to get a look at us. Others lay sleeping on ice flows indifferent to our presence.

Brian Johnston, Surrey Canyon, photo by Jim Gallagher.

We followed increasingly wide shore leads on our route around Wellington Bay all the way to the Ekalluk River – our exit off the saltwater of the Beaufort Sea. We spent a few hours tracking our canoe up the Ekalluk River into Ferguson Lake. This bit of upstream river work saved us from another mile-long portage. Small wood frame cabins are interspersed with ancient stone tent rings and meat caches. This area has been a popular fishing and hunting destination for many generations.

Our entry onto Ferguson Lake would begin 35 miles of lake paddling. We hoped to leave the ice and fog of Wellington Bay behind. Doubt crept into our conversations after we encountered 2 foot thick candle ice within the first few hours of paddling on Ferguson. We traveled on the next day hoping a lake clear of ice lay just around the next point. When the ice-generated fog briefly lifted we saw nearly continuous ice ahead. We paddled, pushed, and dragged our canoe through candle ice and between larger pans of white ice. At the end of a hard day we had covered 12 miles in a crooked route of shoreline paddling, progressing only 6 miles eastward as the crow flies. Much of Ferguson Lake was still frozen and would remain that way for the foreseeable future. We needed to reevaluate our situation or gird ourselves for days of increasingly difficult travel.

In the morning we made the decision to backtrack to open water near the outlet of the Ekalluk River and make arrangements to get a floatplane flight around the frozen Ferguson Lake. Northern Girl arrived the next day. Dave the pilot flew this 1950’s vintage DeHaviland Beaver floatplane. Within 30 minutes Dave shuttled us to an unnamed lake further along our planned route. In a roar of her big radial engine, Northern Girl left us beyond the ice of Ferguson Lake with a week to float and dawdle our way through the remaining 20 miles to Cambridge Bay. We followed an intimate little river connecting a string of unnamed lakes towards our destination.

The ice was gone on Cambridge Bay when we paddled into the hamlet on August 6. The Loran tower that marked the Cambridge Bay skyline for almost 70 years was also gone, taken down the day before. Though the original Loran navigation system was long obsolete, the 620 foot tower had served as a simple visual marker for generations of residents, sailors, and explorers finding their way to Cambridge Bay. I wondered what else changed in the world while I was away. My reentry into civilization was marked by reconnecting the threads of events and relationships left hanging when the floatplane first took flight on the day we left.

Jim Gallagher paddling along ice, photo by Brian Johnston.

Our trip was ending, but others were in the midst of their journeys. We watched two sailboats leave Cambridge Bay headed in opposite directions into the ice of the Northwest Passage. An intrepid Frenchman, Charles Hedrich, arrived overnight in his ocean-going rowboat in his quest to row the Passage. Our own journey felt small in comparison.

The finality of a trip ending gave me pause to reflect on the past month of travel. I didn’t feel like I had been worked like a galley slave as I had felt after past trips. A floor scale confirmed that we hadn’t lost body mass during our travels. Endless high Arctic days darkened what little skin we exposed. We walked among the bones of those who came before us on the land. A new collection of waterways came to life for us from the maps for this far northern island. We quenched our thirst for exploration and paddled ahead of our own mortality for another year.

As paddlers, Brian and I were an uncommon spectacle that raised the curiosity of a few human residents and some seals along our route. The memory of our visit likely faded after our canoe ceased to ripple the water – a fair trade for the memories that we gained. The cold wind and fog off the ice reminded us of the short cold days to come. At 69° North Latitude summer is allowed only a brief and tenuous grip on the warmth of the season.

Jim Gallagher navigating the canoe over a ledge, photo by Brian Johnston.

Trip Statistics

Paddling the Banning River, Surrey River, Wellington Bay, and Ferguson Lake to Cambridge Bay

July 9 – August 6, 2014

The Crew

Brian Johnston, Canada, age 49

Jim Gallagher, USA, age 58

Canoe trips taken north of 60° latitude: 28 combined

The Trip

| Bodies of water traveled on Victoria Island in 2014 |

Miles of |

|

Banning and Surrey Rivers, Nunavut, CA |

135 |

|

Wellington Bay, Beaufort Sea |

15 |

|

Ekalluk River and Ferguson Lake, Nunavut, CA |

43 |

|

Unnamed river and lakes into Cambridge Bay, Nunavut, CA |

22 |

|

Total |

215 |

Beginning coordinates: (Banning Lake) 69°36’27.78″N latitude; 110°13’11.68″W longitude

Ending coordinates: (Cambridge Bay) 69° 6’49.72″N latitude; 105° 3’23.10″W longitude

Notable trip accomplishment: maintained our body weights after 28 days on the trail.

Time on the water: 28 days (July 9 – Aug 6)

Time zone: central

Territory: Nunavut

Hours of daylight encountered: 24 hrs

Planned average daily rate of travel: less than 8 miles (13 km)/day

Days spent wind bound (no travel): 3

Class of rapids run: class 3/4

Class of rapids encountered: up to class 4/5

Banning & Surrey Rivers average gradient: 3 ft/mile (0.56 metres/km)

Precipitation encountered: snow, sleet, and rain

Lowest temperature: 30° F (estimated)

Equipment and Provisions

Watercraft: 17 ft. Pakcanoe (by Pakboat)

Paddles: Aquabound Edge straight shaft paddles, two and three piece construction

Weight of our outfit: 450 lbs. (204 kg)

Gallons of white gas camp fuel consumed: 1 3/8 gallon (5.2 liters)

Books read: 6 combined