Lila Traverse—Testing the Legal Waters in the Adirondacks

by Phil Brown

If you love paddling in the Adirondacks, you put up with the portages. You might even come to regard sore shoulders, scratched shins, and blistered feet as badges of honor, bestowed on those committed to seek out real wilderness. You wear your pain with pride. That said, you’re not a masochist. You’re smart enough to recognize that walking on a muddy, bug-infested trail with a canoe on your head and a pack on your back is not an end in itself. If you could avoid a long, arduous carry, you would. Right?

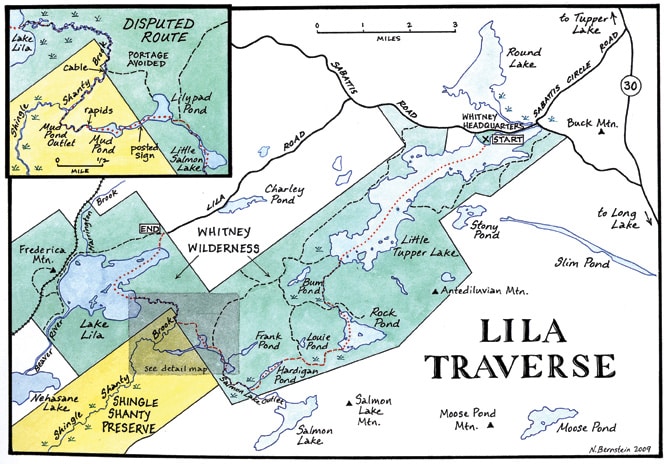

I was thinking such things as I put in Little Tupper Lake in late May for the start of a two-day canoe trip to Lake Lila. I had been meaning to do the Lila Traverse ever since the state bought Little Tupper from the Whitney family in 1998. Now that I’ve done it, I wonder why I waited so long.

Both Little Tupper and Lila are now part of the William C. Whitney Wilderness. On the traverse, you cross four lovely ponds and explore five enchanting streams. Ordinarily, the trip requires four long carries, but I did it in just three.

The last portage trail leads almost a mile from Lilypad Pond to Shingle Shanty Brook. I avoided it by canoeing through private land from Lilypad to Mud Pond and down the Mud Pond outlet to Shingle Shanty. Apart from one brief carry around a dam and some rapids on the outlet, I was paddling the whole time.

You won’t find this variation of the traverse in guidebooks or on maps. The land is posted, and Shingle Shanty Brook has a chain across it. A group called the Friends of Thayer Lake owns the land, while the Brandreth Park Association owns the recreational rights. In the past, the association has insisted that anyone who paddles the route without permission is trespassing. But after researching the law and talking to experts, I became convinced that the public has the right to take this route.

The common law of New York state grants paddlers the right to travel on “navigable” waterways. This right of navigation includes the right to portage around rapids, dams, and other obstacles. It does not include the right to pursue other activities, such as camping, picnicking, and swimming.

If this variation becomes the standard route, one of the best wilderness canoe trips in the Northeast will become even better. For now, however, some legal ambiguity remains. The landowners refused to comment for this story, so we don’t know how they would react if paddlers start showing up regularly on these waterways.

Below is a description of my entire two-day trip. The itinerary can be followed as far as Lilypad Pond. At that point, you must decide whether to do as I did or stay within the public Forest Preserve. If you opt for the latter, paddle across the pond to the north shore to locate the final carry trail. It leads to the stretch of Shingle Shanty Brook in the Forest Preserve.

Little Tupper to Hardigan Pond

Little Tupper to Hardigan Pond

The forecast called for two days of warm sunshine, but the sky and the water were leaden gray when I slipped my canoe into Little Tupper Lake. I started paddling the five miles to Rock Pond outlet, which flows into the western end of the lake. Little Tupper is a wonderful body of water, but I found this part of the trip a bit monotonous. I prefer the intimacy of small ponds and streams.

I found myself fighting the wind, but the breeze kept the black flies at bay. I made the mistake of stopping in the lee of an island, and the bloodthirsty buggers swarmed all over me in an instant. When I put on my jacket’s hood for protection, they pelted it so frequently and furiously that I thought it had begun to rain.

Little Tupper has several islands. The biggest is named Short Island. Not long after Short, you’ll come to a small island with two tall pines growing on either side of a prominent boulder. Rock Pond’s outlet is just beyond this islet.

Entering the marshy stream, I felt embraced by nature. The chatter of red-winged blackbirds, the whistles of white-throated sparrows, and the deep doo-wop of bullfrogs filled the air. Bog flowers decorated the shoreline. In short order, I passed a beaver lodge, flushed a duck, and spied a hawk on top of a dead tree.

You’ll come to a fork about a half-hour up the channel. Bear left for Rock Pond. In another five minutes, you’ll reach a beaver dam. I was able to paddle over the dam, but in summer you may have to get out and drag your boat. A few minutes beyond the dam, look for a signpost on the left. This marks the start of a short carry around rapids and across an old logging road.

It takes only a minute to walk to the road. The official carry trail jogs left, then makes a quick right off the road to lead to the calm water below Rock Pond. I saved a few steps by putting in right from the road. In no time I was at the pond, admiring the views of nearby peaks.

Rock Pond is really a lake, and I had it all to myself, unless you count the one loon and a million black flies. The sun was out, and I had time to kill, so I paddled around the main island and then explored the inlet on the west shore. After this pleasant diversion, I endured the first long carry—nearly two miles to Hardigan Pond.

The trail begins at a tiny knoll on the northwest end of Rock Pond’s western bay. Although there’s no sign, the start is indicated by surveyor’s tape tied to tree branches. The same goes for the rest of the carries. Throughout the portages, you find garish bits of colored tape—red, white, blue, yellow, orange. It’s lamentable that more than a decade after the Whitney purchase, the state has failed to properly mark the carry trails.

I had heard that the start of the trail to Hardigan Pond is mucky. Today it was underwater. I floated my canoe for the first few hundred feet, walking behind. After that, I got onto higher ground. The portage trail follows an old logging road and intersects several other old roads on the way to Hardigan. At each turn, follow the tape. It’s ugly, but you’d be lost without it.

I had heard that the start of the trail to Hardigan Pond is mucky. Today it was underwater. I floated my canoe for the first few hundred feet, walking behind. After that, I got onto higher ground. The portage trail follows an old logging road and intersects several other old roads on the way to Hardigan. At each turn, follow the tape. It’s ugly, but you’d be lost without it.

Even to a non-forester, it’s evident that these woods were logged extensively. Unlike the majestic evergreens ringing the ponds, the trees along the carries are young and skinny, mostly hardwoods. The roads remain wide and grassy or gravelly. Some locals objected when the state designated the tract a Wilderness Area. True, it may not look like wilderness today, but give it time.

Beavers have built a few dams along the road. One flooded the road so much that I put in my canoe and paddled across the water. I got to Hardigan Pond about 6 p.m., more than eight hours after starting my journey at Little Tupper. Before setting up my small tent, I put on long johns, long-sleeve jacket, hat, sneakers, and socks—as protection against the flies. Even so, they often became unbearable. While cooking dinner, I’d often dash to the shoreline to catch a breeze. I ate as quickly as possible, then dove inside my tent. A wise man once said that pleasure is the absence of pain, though I have no idea what he was doing at Hardigan Pond in bug season.

Hardigan Pond to Lake Lila

On my second day, I planned to meet photographer Sue Bibeau at noon at Lilypad Pond. She would be coming from Lake Lila. I figured I had plenty of time, so I lazed awhile in my tent, putting off my next battle with the flies. I’ll spare you the details, but the flies won, and I fled ignominiously in my canoe.

It takes just ten minutes to paddle across Hardigan Pond. The outlet is quite wide but seems to stop abruptly at a beaver dam. Left of the dam is the muddy start of a half-mile carry trail to the Salmon Lake outlet. Fortunately, the trail soon reaches dry ground. A few hundred yards from the start, it turns right and eventually reaches the put-in. Salmon Lake outlet is a delightful stream, with open views of the nearby hills. It has enough current—at least in spring—that you could drift much of the way to Little Salmon Lake, the next destination.

It was already 11:45 when I got to Little Salmon. I quickly crossed the pond and started down the outlet. Shortly, I spotted white tape along the right bank and pulled over, thinking this must be the carry. Then I saw a campsite sign. My map indicated that the take-out was downstream of a campsite, so I got back in my canoe and soon found myself approaching rapids. Apparently, the portage trail did begin at the white tape. Not wishing to wreck my carbon-fiber boat (a Spitfire made by Placid Boatworks), I bushwhacked to the trail and arrived at Lilypad Pond forty minutes late. I called Sue’s name.

Silence

After reaching Lilypad, you can paddle north to find the next carry. However, I paddled west into the broad channel connecting Lilypad to Mud Pond. There I saw a no-trespassing sign posted by the Brandreth Park Association. Although the association owns the recreational rights, these would not supersede the public right of navigation—if these waterways are indeed navigable under the law.

I ate lunch near the sign and waited for Sue. When she didn’t show, I continued as planned. Just after 1 p.m., I crossed the property line. The channel soon widened into Mud Pond. I saw a deer on the shore, staring back at me, and a goose in the grassy shallows, perhaps on a nest. The pond ends at small dam. Below the dam is a short stretch of rapids.

I took out my canoe at a slab of bedrock left of the dam and followed a path to the flatwater below the rapids. The carry took about four minutes. (I saw moose scat on the way.) There is another no-trespassing sign at the end of the portage, directed at paddlers coming upstream.

The Mud Pond outlet below the rapids was plenty deep and wide enough for paddling. It also was quite scenic, gently winding through alders and marshes. Rounding a bend, I suddenly encountered Sue. We canoed together down the rest of Mud Pond’s outlet to Shingle Shanty Brook. At 2:15, we came to the cable strung across the water, with no-trespassing signs facing paddlers coming from Lake Lila. Ducking under the cable, we re-entered the Forest Preserve. Incidentally, this is where the carry trail from Lilypad Pond emerges from the woods.

In all, it took me an hour and ten minutes to cut across a small corner of the Thayer Lake tract, from Mud Pond to the cable. Except for the carry, all of the waterways—the pond, the outlet, and the brook—were obviously navigable in the lay sense of the word. Indeed, they epitomize what I like best about Adirondack canoeing: closeness to nature, ever-changing scenery, remoteness from roads.

As for the carry, it ranks among the shortest and easiest I’ve done. And the law does allow you to portage around rapids and other obstructions.

Sue and I still had a lot of canoeing ahead of us. Over the next hour, we meandered for miles through marshland to Lake Lila. Once on the lake, we had to contend with wind and whitecaps for nearly forty minutes. Finally, we made it to Lila’s beach, glad to be back on land.

A longer version of this article was originally published in Adirondack Explorer Magazine.