An Expedition Across the Arctic Divide: Four Rivers, One Month

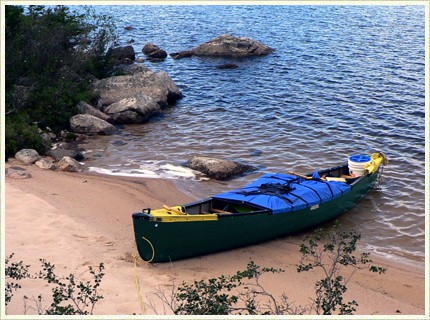

Follow Rob Kesselring and Montana adventurer Pete Lenmark on an ambitious 910-mile arctic canoe trip. The trip began with a bush plane flight to Nonacho Lake in the Northwest Territories. Rob has a canoe stashed on this remote lake 160 miles from the nearest road. From there, things get really remote!

Paddling 290 miles Upstream

Their route takes them 290 miles upstream on the Taltson River and then up an unnamed river to the Arctic Divide. Here they will portage across the divide to the Hudson Bay drainage. They will pick up the Elk River and follow the Elk to the Thelon River and then downstream the Thelon for hundreds of miles and through three giant lakes: Beverly, Aberdeen and Schultz before ending their journey at the small, Inuit settlement of Baker Lake.

Finding the Caribou

The expedition will span the entire range of the Beverly Caribou Herd. This herd has suffered a massive population decline. At one time the herd contained an estimated 450,000 animals, but recent surveys indicate a remarkable and tragic decline of over 90%. Cause of this decline remains a mystery and one of the objectives of this expedition is to study the range for clues and to look for remnant populations.

Documenting Untouched Wilderness

Rob and Pete intend to increase global awareness of one of the last giant and truly pristine tracts of wilderness left in the world. They will travel across an area the size of Minnesota and the Dakotas combined that contains not a single permanent human resident. This transitional boreal forest tundra ecosystem is one of the least studied environments in the world, but it may be short-lived, due to aggressive plans for development in the coming years.

UPDATE:

In the month of July my website uncommonseminars.com had over 5,000 hits on our real time Google map of Peter Lemark and my 760-mile canoe expedition across the arctic divide in the far north of Canada. I want to thank those of you that checked on our progress and followed our expedition on our website and on canoeing.com. It was a challenging trip and knowing people were checking in on us gave us strength. We appreciated your interest and your support.

In the month of July my website uncommonseminars.com had over 5,000 hits on our real time Google map of Peter Lemark and my 760-mile canoe expedition across the arctic divide in the far north of Canada. I want to thank those of you that checked on our progress and followed our expedition on our website and on canoeing.com. It was a challenging trip and knowing people were checking in on us gave us strength. We appreciated your interest and your support.

“So what was the best moment on your arctic expedition?” A friend posed this question to me shortly after I had returned from Nunavut. Full of adrenaline from driving 2500 miles almost non-stop from Yellowknife, I wanted to give him a day-by-day detailed trip report, but “the best moment”? I needed to ponder that. A wry smile came to my face as I recollected the best moment. It had come on July 25, the twentieth day of our expedition at our twentieth campsite.

The day before that perfect moment began at 5:30 am with a brisk east wind. We were able to cook oatmeal in the open, as the bugs were only bothersome if you faced away from the wind. By 7:00 we were on the water fighting the waves and wind on wide expanses of the river and making slow but steady progress. Early on this trip we had wondered whether the predominate wind would be from the West or the East? It’s East. This endless wind made navigation simpler: when in doubt we just put our nose into the wind. The sail stayed stuffed in a sack. On this day, the wind died just as the Thelon River funneled tighter and the current quickened.

The day before that perfect moment began at 5:30 am with a brisk east wind. We were able to cook oatmeal in the open, as the bugs were only bothersome if you faced away from the wind. By 7:00 we were on the water fighting the waves and wind on wide expanses of the river and making slow but steady progress. Early on this trip we had wondered whether the predominate wind would be from the West or the East? It’s East. This endless wind made navigation simpler: when in doubt we just put our nose into the wind. The sail stayed stuffed in a sack. On this day, the wind died just as the Thelon River funneled tighter and the current quickened.

We ran 5.5 miles of rapids that were unmarked on the map. Rapids are not so much a thrill as an obstacle on a remote river. The consequences of a capsize, the possible loss of your canoe and all your gear, keeps you focused and cautious, no whooping and hollering. Still, going downstream was so immeasurably more pleasant than battling upstream on the Taltson River for the first twelve days that we reveled in our good fortune to be moving with the aid of gravity. The sky was hazy, blackened by forest fires far to the south and the air was sultry. We decided to eat lunch in the canoe and this had increasingly become standard procedure. Even on a calm day the current creates enough motion that the bugs are not a big problem especially if you stay in the middle of the river. For lunch we ate crackers or bannock, peanut butter, 5 prunes and a piece of hard candy washed down with river water from our Nalgene bottles. We never went to shore without good reason and by this stage of the trip the Nalgene bottle was used for two purposes. The first time I washed it with soap but Pete convinced me that urine was a sterile solution. So by now we just swished it out.

I can write this next line only because Pete had humbled me earlier on some of the most challenging portages imaginable. He is a pack mule and it is no wonder that when his friends shoot an elk in the Montana backcountry, they call Pete to help pack it out. But on this day, in the rapids, Pete made a bonehead move, a crossbow draw when I asked for a draw and we stuck on a rock, spinned and pinned. We struggled to keep the upstream gunwale above the water but failed and water poured in aft and bow of the center section of our spray cover. The Royalex hull made a sickening groan; it dimpled and started to bend around the rock. We jumped out of the boat and with the force of will freed the canoe from the rock and swam with it through a lively rock garden. I was downstream of the boat and had to work around it before the canoe could make a pancake out of me. Pete was okay and swimming free trying to push off from rocks with his front facing feet. We both kept an iron grip on our paddles. I pulled myself up on the overturned boat and we rode the rapids for 300 yards until we could ease the canoe into an eddy. I am embarrassed to admit that our packing had become a bit complacent and more than one of our “waterproofed” packs took on water. But our gear was lashed in and everything was accounted for except for our sponge. We cautiously paddled downriver to a rocky island where we spent a couple hours drying stuff and letting the hazy sun restore the canoe to its proper shape. We’d be eating bannock from now on, as all our Rye-Crisp crackers had become mush. I was dismayed to discover that the factory cellophane wrapping is not watertight.

It was even more disconcerting to discover that the island where we were repacking straddled the maw of the Thelon canyon. Getting over to the right bank and the recommended portage route, would require a strong ferry. If we failed to hold the ferry angle we would be swept downriver over a breathtaking drop. I had read of people lining the Thelon Canyon, but 2010 was a wet summer and the river was running high, canyon wall to canyon wall. I couldn’t imagine an attempt at lining. It was portage time.

To get the boat out of the canyon we tied the stern line to the bow line and hoisted the canoe up the cliff face. It is a 3-mile portage to the end of the canyon but unlike the two weeks before on the Taltson, the Thelon is one of the most commonly paddled rivers in the far north and there are actually faint portage trails. Still three miles is three miles and we decided, as it was already past suppertime, to carry our personal gear packs, some food and our tent to the end of the portage, camp there, and return in the morning for a second load. Two miles in, we met our first fellow travelers on the Thelon. We had seen no one on the Taltson and one party of four on the Elk. This was a Saskatchewan couple, both professional guides, and she was the first female we had seen in a long time. They were breaking the rules and eating in their tent and we talked as we stood in front of their tent.

In Minnesota there is sometimes an urge to keep distant from fellow travelers, but in the arctic, likely because encounters are so rare, it is just the reverse. It may seem rude that they did not invite us into their tent but it wasn’t. It may seem rude that we interrupted their dinner but it wasn’t. It is a happy shock to meet new people and to hear two new voices waft through the mosquito netting. A female voice was especially soothing. We would replay the dialog for the next several days as we paddled and I am sure they did too. It’s a different world when you go weeks between visitors. I could have talked for an hour but Pete was anxious. Somehow the blackflies had severely compromised his headnet and clothing. As you would expect there was a swarm around his head trying to get in. There was also a swarm inside his headnet. His pants had also been penetrated. I think the bugs had found entry though mesh pocket liners. Earlier he had wondered why his pockets were puffed out. Reaching in he shoveled out a handful of blackflies. Pete had taken to slathering his scrotum with DEET, there are some places you just don’t want to get bit. But even when they are not biting, black flies, under your clothes, just crawling all over you, will give you the heebie-jeebies. So I had to say goodbye, but not before they told us that some canoeists run the river from this point and avoid the last mile of portaging. They had scouted it earlier and decided the rapids were too high to run and they were going to portage tomorrow.

Pete and I decided to check it out. It was the only argument I had with Pete on the entire expedition. He wanted us to carry our packs when we scouted the rapids so that if we decided to portage we would at least have one load over the portage. I wanted to leave our packs near the Saskatchewan tent because I wasn’t walking all the way down there to decide whether or not to run this rapid, my only question was how to run it. If someone had done it before, we could do it. Pete made all the land decisions and I made all the water decisions. In that this was both a water and land decision it created an impasse, but in the end, he caved.

I think he was feeling bad about us dumping in rapids earlier but he shouldn’t have. He saved my bacon a few days before when he volunteered to carry the canoe over the arctic divide. The first half-mile of that 3-mile portage was through an untracked tamarack swamp. It was a super-human effort by Pete to get a canoe through that swamp. A few days before that he blazed a one-mile portage over cobble and muskeg that left me pale and exhausted. And again he took the canoe, (l carried the 88-pound food pack).

It was raining in the canyon as we pitched the tent but not hard enough to knock down the black flies. When we finally crawled into the tent at least a thousand black flies came in with us. This is no exaggeration. We lit two insecticide coils and listened with glee as they fell like tiny hailstones. When we pulled off our clothes, hundreds more black flies tumbled out. I didn’t check out Pete’s scrotum (there are certain things you just don’t do) but my belly button looked like a gunshot wound. We broke the rules and ate in the tent. Any grizzly bear would have too much sense to be anywhere near that bug infested canyon.

It was bedtime. My inflatable pad had punctured on day 3, so I no longer bothered with it. I just rolled out my sleeping bag and crawled in. Somehow bugs from the previous night were still active in the bag so I spent a few minutes smearing them. Almost midnight, it was twilight in the canyon. The Thelon River is south of the Arctic Circle so although it never gets dark in July, it does get dim, especially with rain and smoke in the air. Lying on my back, just nylon between the ground and me, wet, bug eaten and tired. I stretched out my right leg. This triggered the most excruciating cramp of my life. It went from my toes to my thigh like a bolt of lightening that wouldn’t quit. I can hardly bear it. I reach down with both hands to massage my hamstring and wham my left leg cramps up. A double cramp, both legs in total spasm. I am in paralyzing pain. I should have drunk more water during dinner but I had already peed in the Nalgene water bottle so that was not a viable option. I was wondering how long cramps can last and then I start shivering, uncontrollable shivering. I am bouncing around the tent. Should I rouse sleeping Pete? Instead, I just pass out.

I wake up, it’s 5:30 and the sun is high and I feel pretty good. And from 5:30 to 5:31 is the best moment of my trip. I am alive and I am traversing one of the largest and most magical wilderness landscapes in the world, it doesn’t get any better than that.

This canoe expedition from Nonacho Lake to Beverly Lake was more about more than just adventure. We traveled upstream on the Taltson River to the Arctic Divide and I wanted to understand why this was one of the least traveled historic routes. On the map it looked easier than Pike’s Portage. I also wanted to experience the dynamics of traveling the arctic in a more traditional way. Typical far north recreational canoe trips consist of a bush plane drop-off at a river’s headwaters and then a pick-up downstream. I also wanted to prove that you could still paddle the far north without spending a lot of money on charter aircraft. Instead, we would use sweat equity to move from watershed to watershed. Most of the remainder of this article will focus on another major goal: the search for the lost Beverly Caribou Herd.

In the 1970’s when I lived in the Northwest Territories the population of this herd, by some estimates, was over 350,000. Recent counts have put the number below 40,000 and maybe even lower. Caribou are the icon of the North and a key animal in the North’s circle of life. Wolves depend on caribou, especially in the winter. Foxes and ravens depend on wolf kills for carrion also in the winter. Grizzly bears feed on calves in the early summer. I have noticed that even hares travel with the caribou in winter because the big deer break trails in the snow and their browsing reveals forage. Bald eagles arrive early in the spring when the lakes and rivers are still icebound, and I have seen them feed on caribou wolf kills. The demise of the caribou will empty the land; already grizzly bears have been sighted in Fort Smith and northern Saskatchewan far from their tundra home.

When I worked at Nonacho Lake during the summers of the late 1970’s, caribou droppings peppered the landscape. When fisherman wanted a shed antler to take home, a short walk on an esker would yield a half dozen. The aboriginal people of area, the Chipewyan Dene, claimed that the herd had wintered in the Nonacho Lake area as long as they could remember. Pre-historically the Chipewyan Dene Indians were truly people of the deer and almost all aspects of their culture revolved around the caribou. Even to this day caribou is an important food source for the Dene in the communities that border the Beverly Caribou Range. The first several days of our expedition were spent in that traditional caribou winter range and yet evidence of caribou was rare. Even on the shores of Nonacho Lake, musk-ox tracks and droppings far outnumbered evidence of caribou. When we reached the Elk and Thelon Rivers, prime summer habitat of the caribou, our search yielded little. Moose outnumbered caribou and when we did encounter caribou they were alone and appeared sickly.

I have talked with many people about the decline and everyone has a different answer. First there is denial. In the 1950’s and 60’s there was another fear of a massive caribou decline and it turned out that caribou had merely changed their migration routes and were not gone at all. This embarrassed the Wildlife Service and vindicated the Dene. In fact, caribou population surveys have always been suspect. Their huge range, the cost of charter aircraft and sloppy science has left a legacy of very dodgy caribou population statistics. However, it is hard to imagine that this is the case in 2010. New technology including satellite transmitters on collars, sophisticated aerial photography and comprehensive airplane surveys substantiates current populations more accurately than ever before. Anecdotal evidence also supports the decline. If the caribou are still here, where are they? On our trip, which spanned 750 miles, we saw 3 caribou. Denial of the decline has slowed the response and could have a negative impact on the herd’s recovery.

Apparently it is still possible to find remnants of the herd. In those pockets the high density of the caribou is reminiscent of days gone by. But a small area with a high population density might mislead hunters into thinking the animals remain abundant. Native people have already been put on the defensive as many people accuse the long history of unregulated hunting by First Nations people as the cause of the decline. I am often told that wanton killing of caribou and access to repeating rifles and snowmobiles by native hunters is the cause of the decline. I reject this argument. Dene hunters have had repeating rifles for over a century. Wasteful or excessive harvesting of the caribou tend to be isolated and exaggerated cases. Subsistence hunting by aboriginal people has a long and harmonious history and the numbers just don’t justify blaming hunting for this problem. Rifles and gut piles make for dramatic photographs but do not explain the huge decline in numbers. I can remember massive hunts in the 70’s at a time when the herd was increasing in population. However, restricting caribou harvest by native people and eliminating sport hunting of caribou might be a necessary step for the herd to recover. It will be difficult to implement such restrictions because many First Nation people depend on the caribou. But for these people the caribou transcend diet concerns. Their culture has a timeless and spiritual link with the caribou and many tribal leaders are alarmed and concerned by current trends and are active in finding the cause and the solution to the disappearance of what, for their long history, has been their lifeblood.

An increase in insect life has also been suggested as a reason for the herd’s decline. People have told me that caribou lose a pint of blood a week to mosquitoes and black flies. This may be true. We hit some buggy days on the Thelon but no worse than what I experienced in the 1970’s. As early as 1770, Samuel Hearne described the onslaught of insects in great detail. Researchers new to the area may think bugs are more numerous than ever, but I do not believe any research corroborates that opinion. There may be an increase in parasites that is affecting the health and fecundity of the herd. This is something that needs to be studied. Woodland caribou were once found in the BWCAW but scientists believe that brain parasites transmitted by Whitetail deer were part of the reason for their demise.

Wolves are major caribou predators and have been blamed as a cause for the decline. But just ten years ago the Toronto Globe and Mail newspaper ran a series of stories on massive wolf hunting and trapping in the Rennie Lake area. At that time, wildlife biologist and canoe guide, Alex Hall, told me that dens that had been occupied for years were empty. He feared the wolves would be totally eliminated. It’s hard to imagine that just a few years later wolves are to blame for the missing third of a million caribou. We saw two wolves on our trip and tracks were common. Canada Geese moult on the riverbanks and they are an easy meal and so draw wolves. I saw many more wolves in the past than on this trip. Even so, wolf control, especially on the calving grounds, may play an important role in the herd’s recovery in the years to come.

Herd animals exemplified by the caribou are a paradox. Their sheer numbers suggest that extinction would be impossible but they depend on their population density to survive. The herd moves to the calving ground en masse. Many of the wolves that have followed the caribou during the winter will need to stop, den up and whelp their pups. On the calving ground so many calves are dropping at once that the remaining gluttonous wolves cannot keep up with the buffet. But as the herd shrinks the calving process is imperiled. Some biologists suggest that the Beverly Herd has already become so small that surviving caribou are leaving the area to join the Bathurst and Qamanirjuaq Herds where the greater numbers provide that essential protection during calving and even during day-to-day travel. If the herd numbers become too small a population rebound may be impossible.

The cause may be more global than local. Vegetation grows slowly in the North and can absorb and concentrate toxins from the atmosphere. Just as old Lake Trout have accumulated toxic levels of mercury in pristine Northern lakes, it may be possible that caribou forage has become contaminated to such an extent that the animals are aborting calves or being poisoned. The three caribou we saw on our expedition did not appear to be spry. In fact, one was lying down and did not even stand up until we got out of our canoe and approached it on foot. This is the scariest possibility because the pollution source may be thousands of miles away and impossible to curtail in time to save the caribou. The fact that other caribou herds across Canada and Alaska and reindeer herds in Russia are also experiencing population declines adds credence to this unhappy hypothesis.

Industrial disturbance has also been suggested as a cause for the decline. Winter roads have increased hunter access and mineral exploration may have stressed the caribou. Although a much stronger case for that could be made for animals in the Bathurst or Porcupine Herds. To this date the Beverly Herd range remains pristine wilderness. It remains as one of the largest uninterrupted tracts of wilderness in the world. This may end soon with the construction of the proposed Deze Energy Corporation powerline around the east arm of Great Slave Lake and the proposed winter haul road to Nonacho Lake. On our expedition we did not see another person, or hear a floatplane until the nineteenth day. We found far more evidence of pre-Columbian people: tent rings, stone points, wedges, flakes, knives and hammerstones than of more recent land use. The upper Taltson River may be the wildest river on the planet. I remember when someone asked polar explorer Ann Bancroft what she did when she got to the South Pole. She replied, “I had a hamburger and French fries.” There is a research station right there on the pole! In our 750-mile route there were no hamburger options. Over four thousand people have climbed Mt Everest but there are tributaries of the Taltson River that have never been paddled, at least not in historic times. The wild nature is the real value of this huge incredible tract of land and the vanishing caribou winnow away some of that value.

Another suggestion explaining the caribou decline is that because of global climate change the summer is coming earlier to the tundra and plant life is adapting faster than the mammals. The sprouting of highly nutritious forage is happening earlier and by the time the caribou have arrived these plants have gone to flower and caribou are missing key nutrients during the days they need them the most. This sounds plausible but on our journey we had no way to confirm that phenomenon. In 2010 the lakes were ice-free early and the days were hot and the water warmer than any far north trip I can remember. But whether earlier and warmer summers would adversely affect plant growth is not certain.

I witnessed a different consequence of climate change. We traveled through many square miles of the winter range of the Beverly Caribou and on the way out we flew over another big swath of winter range. The astonishing characteristic of the landscape was the amount of recently burned-over territory. Although many factors may play a role I believe the biggest factor in the decline of the herd is widespread wildfires in the winter range. Caribou depend on the lichens that grow in a mature open-boreal forest. We saw a dozen moose on our trip and they prefer the vegetation of a disturbed forest. Muskoxen once thought of as tundra animals are common in the parklands that have been created as result of these widespread fires. If caribou are not finding sufficient browse on their winter range it is possible the cows are reabsorbing their calves. This would explain why so few calves have been seen in recent years. Without calves to replace the attrition of adults it would be easy to understand how the numbers could drop precipitously. Widespread fires in the winter range may be part of a natural cycle and there is some evidence of caribou die-offs before. It is always tempting to believe that nature is static and that vegetation and the variety and populations of animals remains similar year after year, decade after decade, century after century. This simply is not true and sometimes humans complicate these processes of natural change by trying to create stability in a system that is inherently dynamic. But the scope of these recent fires may also be the result of human induced longer, hotter summers resulting in thawing permafrost and a drying of the landscape that is unprecedented. Climate changes that come so fast, whether natural or unnatural, can create dramatic shifts in ecosystems. The fact that the southernmost caribou herds seem to be experiencing the most extreme caribou declines suggest that increasing warmth, one way or the other, could be the major determining factor and one that will unlikely reverse in the near future.

A positive trend is that the caribou decline is front-page news in the North and that the Wildlife Service and the Dene and Inuit are working together to research and reverse the decline. Efforts in the next few years will be crucial to the caribou’s recovery. Even in the best scenario it will be a long time before the Beverly Caribou Herd again stretches from horizon to horizon, as far as the eye can see, but it remains possible.

This was my sixteenth canoe trip north of sixty degrees latitude. It wasn’t the most scenic, the most exciting, the most fun, even the most successful, but I think it was my favorite. To push so hard and to travel such distance through untracked wilderness on a planet that seems increasingly crowded and sullied by human greed and ignorance was an amazing blessing and I often reflect on the journey to find my center and my spirit.

Many canoe enthusiasts are interested in gear and provisions. Here is the top ten list for our most valued gear and chow for a month in the Far North:

1. CCS Guide Pack: Although at 88 pounds it was our heaviest pack it was also the easiest load, with a great suspension system and impeccable attention to design and detail

2. Bending Branches Expedition Plus Paddles: We used and abused these paddles for a month up and down rivers. They remain as good as new and are unquestionably the best expedition paddles made.

3. Adventure Eggs: These will change the way you think of dried eggs. Nine eggs fried together with a dollop of lard and pre-cooked bacon was by far our best meal. We had it every three days and looked forward to it, almost insanely.

4. 27-foot 3/8 inch floating rescue lines for the bow and stern. Expensive and worth every penny. Expert trackers and liners may want longer lines but how many expert liners and trackers are there? 27-feet was perfect for us. Lines must be attached to the canoe below the waterline.

5. The Tilley Hat: It keeps you dry, cool and the chinstrap keeps it from blowing off. Outperformed Pete’s Stetson nine days out of ten.

6. MSR Whisperlight stove. It is a miser on fuel, dependable and kicks out the heat. Most of our campsites were on sandy beaches but the Whisperlight never clogged, never disappointed.

7. Bannock: You cannot beat fresh bread on the trail.

8. SPOT satellite transmitter: Dropped, dunked and depended on. Sent a safe message every evening without fail.

9. The center section of a CCS spray cover: I prefer an open canoe but three times this cover helped us avoid catastrophe.

10. Nalgene water bottle: I only wish I had brought two of them.

A version of this story appeared in the Fall 2010 Boundary Waters Journal

Rob Kesselring is a frequent contributor to canoeing.com. His books: River Stories and Daughter, Father, Canoe, Coming of Age in the Sub-Arctic, are available at ShopCanoeing.com.